We get lots of logical e-mail from our readers. One theme seems to go something like this: “Why don’t the manufacturers take a modern sportbike, relax its ergonomics, and give it detachable luggage?” There are apparently plenty of “ultimate sport tourers” running around with bars a bit too low, pegs a bit too high, and fairings a bit too small. Seems logical enough, but the manufacturers never listen . . . or do they?

Lately, Yamaha seems to listen to customers (existing and potential) better than most. Expanding its motorcycle sales market share in the U.S. from thirteen percent to twenty percent in the last six years, Yamaha has successfully, and consistently developed new models that either set new standards within a category, or fill a niche unfilled by competitors. Sure, you’re thinking about the R1 sportbike and, perhaps, the YZ400F four-stroke motocross machine priced for the masses, but what about the little TTR125 dirt bike. Yamaha stepped in and created a slightly larger and more powerful air-cooled, four-stroke, off-road play bike, with an optional front disc brake. In the process, it filled a niche that was staring everyone in the face, but only Yamaha made the move to fill it.

Let’s get back to the idea of taking a modern sportbike and relaxing its ergonomics to create a reasonably comfortable sport tourer with extremely high performance. Although plenty of enthusiasts have been asking for such a bike, American sales figures haven’t supported it. Manufacturers look at the sales in the “sport tourer” category, and they yawn. I have been told this more than once by more than one manufacturer. My response is always the same. Give Americans better product within the sport tourer category, and unit sales will increase dramatically. Prior to the 2002 model year, the leading sport tourer machines were, for the most part, quite dated. Indeed, two of the key entries in this category were designed more than a decade ago (that is about to change with Honda’s introduction of the 2003 ST1300). In other words, I argued the preposterous notion that better, and more current product within the sport tourer category would lead to increased unit sales in that category. The reaction? Another yawn.

Which brings us to the subject of this MD Ride Review. Yamaha introduced the FJR1300 to the European market more than a year ago. Unfortunately for U.S. enthusiasts, they could only look on and drool at the bike and its design brief. It appeared to be the embodiment of the “sport bike with hard bags” concept, but Yamaha chose not to bring the model to the United States. The rationale must have gone something like this: “We don’t think a Hayabusa-engined, sport tourer with state-of-the-art chassis, suspension, adjustable windshield and hard bags will sell in the United States, because unit sales in the sport tourer category aren’t very strong.” Once again, the “brilliance” of the U.S. product development analysts left me, and many others, wondering whether we were from the same planet. Well, Yamaha has had a change of heart, and the FJR1300 will be a member of the U.S. line-up for 2003. The timing of its release, and the terms upon which you can obtain one, were discussed by MD on March 1, 2002. That article also rehashed some technical data, and provided some studio photos of the machine.

Lo and behold, MD had the chance to ride one of only four FJR1300s here in the U.S. for several days (and several hundred miles) last week — solo, with the bags removed, with the bags installed, with the bags full, with and without a passenger. Heck, we even took the time to write down the gas mileage figures (expect 40 miles per gallon, or so).

Before we tell you our thoughts on the machine, let’s talk about the hype. Yamaha calls the FJR1300 a “supersport touring” bike, as opposed to a sport touring bike. Yamaha also says the FJR1300 is another “category defining” motorcycle that “explodes the category” (not quite sure how those two statements fit together, myself, but my logic is flawed, remember?).

Leaving, once again, the world of over excited press representatives, and back in the real world, the FJR1300 almost delivers what American enthusiasts expected when all the drooling began a year ago. The bike hauls ass, and is exceedingly comfortable, but doesn’t handle as well as we expected it to.

The reason it hauls ass is the purpose-built, 1298cc, liquid-cooled, four-stroke, in-line four-cylinder engine, featuring double overhead cams and a sixteen-valve cylinder head. With ceramic composite cylinder coating, carburized rods, forged pistons, dual counter balancers and electronic fuel injection, this “clean sheet” design was intended by Yamaha to put the FJR1300 at the top of the engine performance heap (that’s a strange way to put it) in the “category”.

Moving to the handling department, Yamaha has blessed the FJR1300 with a sportbike-like twin-spar aluminum frame with (we are told) sufficient stiffness for precise and agile handling. The suspension includes massive 48mm front forks, adjustable for preload, rebound and compression damping, as well as a rear shock adjustable for rebound, with a two-stage, remote preload adjuster.

With shaft drive, the big FJR promises quiet, low maintenance operation — ideal for touring duties. The drive housing is neatly molded into the aluminum swingarm. That drive system is twisted through a five-speed transmission.

The operation of the neat, thumb-controlled, adjustable windshield was illustrated in our article on March 1, 2002. Similar to a design available on BMW’s popular sport tourer, the R1150RT, Yamaha saw fit to include this feature despite a clear goal to minimize the dry weight of the FJR (and maximize its handling characteristics).

Other touring-appropriate features include a huge 6.6 gallon fuel tank and (standard in the U.S.) detachable hard side cases (each of which will swallow a helmet).

Brakes are sourced from the original R1 and feature four-piston calipers gripping dual 298mm rotors in front. A large 282mm rotor in the back is gripped by a single two-piston caliper.

Yamaha claims 145 crank horsepower and 93 foot/pounds of torque pushing a dry weight of 522 pounds. Riding the FJR1300 doesn’t lead one to dispute these claims, although the wet weight (all fluids except fuel) should be at least 560 pounds.

Engine response to your throttle hand is smooth and predictable, and largely without the sudden surging associated with many fuel injected engines. From below 3,000 rpm right through redline at 9,000 rpm, the FJR pulls without any sudden steps in power delivery — just one, long effortless thrust that mimics a large caliber bullet with a passenger seat.

Indeed, for a machine with such a large spread of power (five gears is much more than enough — trust us), the acceleration is breathtaking. Our guess is that the quarter mile would flash by in the mid-ten second range, probably about as quick as Kawasaki’s new ZZR1200 (which contains a ZX11 motor on steroids, in effect). Undoubtedly, much more motor than you need, and just about as much motor as you want.

The FJR delivers this thrust with the precision and refinement of a bike powered by a modern, fuel injected engine that has been very well sorted by the factory. For a fuel-injected bike, off/on throttle transitions are quite good (though not perfect) and despite some vibration above 6,000 rpm (which arrives at 110 miles per hour in top gear), the engine gets an A. No, make that an A+.

The ergonomics of the machine remind one of a German sport tourer (such as a BMW — Yamaha may have benchmarked the R1150RT, known as the R1100RT at the time). The rider seat is very comfortable, utilizing a dual density foam. The peg/seat/handlebar triangle is also comfortable, although the hand grips initially feel a bit tall and close together (again, somewhat like a German bike). Longer trips (the longest stint in the saddle we had was roughly 150 miles non-stop) leave the rider relatively fresh and relaxed, in part due to the adjustable windscreen.

That windscreen works quite well, particularly if you are under 6’1″ tall, or so. I am approximately 5’11”, but I have a long torso and short legs. I sit fairly high in the saddle, as a result, and I had some minor buffeting at helmet level with the windscreen in its highest position on the freeway. Riders with shorter torsos (that includes you, Willy) find a relatively still pocket of air. Like any effective windscreen of this size (in its extended position), there is a fair amount of vacuum pulling the rider forward (as Willy put it, the bug splatters will be on the back of your helmet, not the front). The only gripe in the comfort department concerns grips made from a relatively hard compound, that can become uncomfortable on longer trips. This would easily be remedied with after-market grips, of course.

When you have occasion to use the transmission (you hardly ever need to — fourth and fifth gear get you almost everywhere, from 15 miles per hour to well over 100 miles per hour) it shifts positively, but can be a bit clunky, particularly, in the lower gears. We do not recall missing a shift.

The suspension does its job fairly well, particularly the fork. The springs inside the massive, 48mm tubes are well damped, and there is a good range of adjustment available. We did play with the rebound adjustors a bit, but found a setting that was very compliant, yet reasonably controlled. The shock, on the other hand, does its job reasonably well in touring mode, but could use more adjustment options. The two-stage pre-load adjustor, when set on its harder setting, doesn’t provide enough spring preload for heavier passengers. Indeed, we preferred to run the bike with the shock preload set on “hard” even with a single rider aboard, because the bike seemed to handle better with the additional ride height in the rear.

Handling is always a difficult subject to discuss in the sport touring context. “Sport tourers”, in the minds of many, cover a very broad spectrum of motorcycles. On one end, you have a Kawasaki ZX-6R with a double-bubble windscreen and a tankbag (which, believe it or not, makes a remarkably comfortable street mount) with a racing pedigree that includes the World and AMA 600 Supersport titles. On the other end of the spectrum, you have the much larger, much heavier (more than 200 pounds heavier, in some cases) “near-luxury” sport tourers. Some of these, like the FJR, have hard luggage and shaft drive as standard equipment. None of the bikes at the near-luxury end of the spectrum handle like the ZX-6R, obviously.

We did our best to judge the FJR’s handling against bikes offering comparable luxury. This is not always easy, particularly, with one of our testers (Willy Ivins) having stepped off a race track and his 125cc two-stroke GP bike just prior to riding the FJR (Willy’s 125 GP bike weighs about as much as a saddlebag).

With our expectations properly calibrated (including, removal from our brains of the Yamaha pronouncement the bike was so good it would “explode” things), we were, frankly, still disappointed in the FJR’s handling. The FJR will handle just fine for most of the riders who will purchase it. It goes where you point it, and holds a line reasonably well through corners.

The FJR did not feel as “planted” or sure of itself as we had expected, however. Chassis flex could be to blame, because, at times, we felt an oscillation travel from the steering head area back through the frame. Although noticeable with a light fuel load, this problem seemed more pronounced with a full tank of gas.

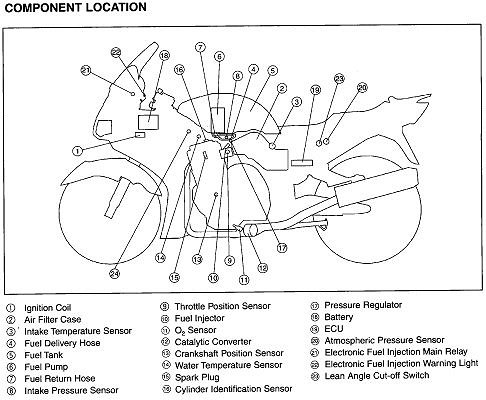

With the frame design by Yamaha appearing very stout, both Willy and I were puzzled by this. We were still puzzled until, by chance, we noted the location of the FJR’s battery, and began to investigate the location of FJR components that significantly affect centralization of mass and polar moment (see definition in the automobile context here and here). The illustration at right provided by Yamaha shows the location of key components, and the story it tells about center of gravity, and the location of dense/heavy components, is perhaps the reason for our handling concerns. Note the location of the airbox identified as component 2 (low density/low weight), the fuel tank and fuel pump identified as components 5 and 6 (high density/high weight) and the battery identified as component 18 (perhaps the most dense and heavy, per square inch, component). The unusual and greatly de-centralized location of the battery — suspended to the side of the right fork leg — is better illustrated in the separate drawing below.

Overall, the FJR exhibits less than precise responses to aggressive “sporting” steering input. Mid-corner bumps also cause the chassis to wallow a bit more than a supersport tourer should.

Nevertheless, as we stated earlier, the handling is stable and predictable enough for most riders looking for a near-luxury sport tourer. It simply doesn’t rise to the levels we expected or, for that matter, wanted the FJR to exhibit. The bottom line is that the motor well deserves the “supersport touring” label given by Yamaha, while the handling does not.

The FJR is a good looking bike with a great motor, excellent ergonomics and loads of convenient features, but curious engineering decisions seem to be the cause of handling characteristics that fall below our expectations.