If you wear a full-face helmet, chances are you chose this type of helmet for its protective qualities. But what about the difference in levels of protection between different makes and models of full-face helmet? In the U.S. there isn’t much information to go on. Helmet safety certification uses a pass/fail system: a helmet either earns a DOT-approved (or, in some cases, Snell-approved) rating or it doesn’t. In the United Kingdom that’s changed with the government’s “Safety Helmet Assessment and Ratings Programme,” better known as SHARP.

The key word there is “Rating,” as in the 1- thru 5-star rating that SHARP assigns to helmets. According to the program, the more stars, the better protection a helmet can give. SHARP is “unique in providing a scaling to helmet performance,” says Anna McCreadie, of the U.K.’s Department for Transport, the government agency that conducts the SHARP testing. The U.K. government created SHARP in the hope that it would arm motorcyclists with more knowledge about the helmets they choose. As McCreadie explains: “SHARP is a comparative test designed to give motorcyclists more detailed information about the likely performance of different helmets in a collision. All the helmets available for sale in the U.K. must meet certain minimum standards—SHARP gives consumers information about how well helmets perform beyond those minimum standards.” SHARP tests have found differences in performance of as much as 70 percent between high- and low-scoring helmets.

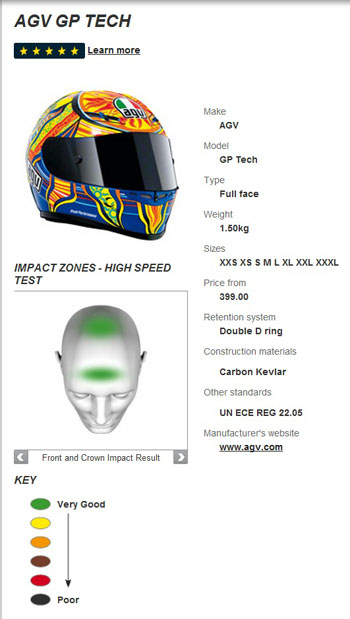

In addition to rating each helmet between 1 and 5 stars, SHARP provides diagrams showing the specific impact areas tested on the helmet. The diagrams depict regions of the helmet, for example the forehead or temples, and use color codes to illustrate how well that portion of the helmet fared in testing. A helmet may have done well in the forehead area (thus receiving a green color code), but only marginally in the temples (a red color code). Again, the philosophy is that more information is better.

SHARP is also unconventional in that it tests only helmets purchased directly from retail outlets. SHARP believes that it is important to ensure the helmets tested are the same as those available to the public. In contrast, organizations like Snell conduct their testing on sample helmets submitted by manufacturers. Snell does, in addition, test random samples of helmets meant for sale or distribution to the general public, but this is not the sole source of its test helmets – as is the case with SHARP. Indeed, manufacturers often do not even know that SHARP is testing their product. This is another difference from Snell, where manufacturers initiate the process by requesting that Snell test their helmets.

Manufacturers are not brought into the process until after SHARP has conducted its testing. They are advised of the SHARP rating before it is published and they can lodge an appeal if SHARP’s measured data does not match what they have seen in development or production testing. The goal is to ensure that the SHARP rating is representative of the helmet’s performance. McCreadie explains the process: “We share our test data with [the manufacturers], which provides an external quality check. If a manufacturer can show clear differences between their own data and that provided to them by SHARP, we will carry out repeat tests which they are invited to witness. The outputs from those tests are final and are used to validate the published rating.” Ultimately, SHARP’s results are released whether or not the manufacturer agrees with them.

As for SHARP’s test regimen, it is extensive. SHARP personnel conduct 32 tests on seven helmets across a range of sizes for every helmet model. The tests are conducted by impacting each helmet against two types of anvils, one to represent flat surfaces and one for curbs. Some of the tests are linear, where the helmet is impacted ‘head on’ in various impact zones ranging from the front, top, back, right and left sides. Other tests are oblique, measuring the helmet’s frictional properties as it glances off an object at an angle (think helmet bouncing along the pavement while a rider is sliding). In addition, SHARP touts the fact that its tests are carried out at three different speeds (one at the ECE standard, one above and one below) to ensure that the helmet provides good protection during both high- and low-severity impacts.

When the testing is complete, SHARP compares the results with real-world injury data from the COST 327 study (the most thorough investigation of motorcycle crashes conducted in Europe). This comparison leads to the final SHARP star rating. Suffice it to say, the process is rigorous—of the 247 helmet models SHARP has rated so far, only 30 received the 5-star rating.

So, just how useful is SHARP for would-be helmet buyers in the U.S.? The answer depends on which helmets you’re considering. Many of the helmets sold in the U.S. are not sold in Europe, and vice versa. For instance, I recently acquired a SNELL-approved Bell Star helmet. Though comfortable and confidence-inspiring, my new Bell Star has not been tested by SHARP. In fact, Bell is an entirely different company in the U.S. than its same-named counterpart in Europe. So U.S. buyers must be savvy when using SHARP. If you want to rely on a SHARP rating, you may wish to check with the helmet manufacturer to be certain the model you are considering is the same as a comparably-named (or somewhat different named) model sold in Europe. That way you know that the one SHARP evaluated is the same as what is available in the U.S. SHARP’s ratings can be found at http://sharp.direct.gov.uk/.

Though SHARP appears to test only a small number of U.S.-market helmets and therefore has limited applicability for buyers in the U.S., its approach seems to be valuable. It gives riders more information than a simple pass/fail rating, thereby allowing them to consider the relative safety of one helmet compared to another. It could be time for the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration, which produces the DOT standards in the U.S., to consider a numerical system similar to the SHARP program. The rating system would not have to be a substitute for the minimum pass/fail standards, they could remain in place. Instead, like SHARP, the system could evaluate how helmets perform above and beyond the bare minimum standard for a passing grade. This might be at least as valid a consideration in buying a helmet as whether to go with stripes, stars, or skulls on the graphics.

We do realize, of course, that not all helmet manufacturers necessarily agree that the SHARP testing methods are valid, or that the conclusions reached by SHARP are valid (this could apply to Snell and DOT as well). Nevertheless, SHARP appears to be a good faith effort to provide valuable information to consumers.

Courtney Olive lives in Portland, OR where he and the Sang-Froid Riding Club excavate the essence of motorcycling.

This is a great resource, though I wish I had come across it earlier since it seems like this has been up and running for a couple of years. I think it further shows that in Europe motorcycles are an accepted part of the transportation matrix and therefore safety is a factor whereas here in the US motorcycles are seen as toys and playthings. It also doesn’t help that the AMA is still mired in the debate over helmet use in general. Until we can finally accept that helmets are not optional we aren’t going to see this type of comprehensive testing which is too bad since I for one would rather import a Euro helmet that meets these standards than put my trust in the one dimensional sticker that the US requires. I hope that they continue to test a broad range of helmets; I also hope that the mainstream media picks up on this and starts to push for this kind of program.

Fantastic. It is amazing that something like this has taken so long to develop. Wish we had it here in the States.

I have had real world testing on two Shoei helmets. One, an RF900 in a street incident @ 50 mph. The other, an X-11 on the racetrack @ 80mph+. In each case, the helmet died and I lived. At the racetrack (Oct, ’11), I hit my head (helmet) hard enough to lose consciousness for about 5 minutes. I think that means a concussion but I had no nausea later and had no lasting effects that I ever noticed. I’m not sure how a lesser helmet would have performed but those Snell approved Shoeis have done very well by me. I hope I never “field test” another one.

I’ll have to agree with Tom on this one. Kudos to the Europeans for at least trying to make a better product for all motorcyclist through testing. As far as I understand the current DOT standards. The US goverment does no testing, and only sets standards for construction. Allowing the manufactures to do there own testing. It’s like letting the inmates run the asylum, while our elected officials are only worried about there next re-election campaign. For motorcyclist here in the good ol’ USA, it’s your money and buyer beware.

Sorry, that should have been that they trade off real world low speed safety for high speed safety.

Looking through the SHARP ratings the thing that jumped out at me was the ratings Arai helmets. They were all given pretty mediocre ratings. The European Bell helmets all had 5 star ratings, if I remember correctly. The Caberg helmets seemed to do well overall, even with their lower priced helmets.

From what I’ve read, the Arai’s don’t do well in SHARP testing because they have been designed with the SNELL tests in mind. The SNELL tests are at higher G’s and they test how well the helmet does in multiple hits in one area. To pass those tests the helmet has to have stiffer linings, which means that they have less give in lower speed hits. So doing well in SNELL trades off high speed safety for real-world lower speed safety. SNELL helmets may be better for racing, but ironically lower priced helmets with softer linings might be safer for street riding.

“High speed safety.”

A Snell helmet will protect you from a head on crash into a brick wall at 25 feet per second, about 17 mph. Think curb or asphalt from a fall or a cold rolled steel 18 wheeler truck bumper. Well under the top speed you can attain on a bicycle. Softer helmets will apparently protect you from the lower speeds of real-world riding, say like 14 mph.

Your choice of speeds that you attribute to various helmet standards are not apropos of anything.

It is a matter of the amount of energy absorbed by a helmet at various speeds. According to this article:

http://www.westcoastweasels.com/archives/PDF/Blowing_the_Lid_Off.pdf

“The European Union recently released an extensive helmet study called COST 327, which involved close

study of 253 recent motorcycle accidents in Germany, Finland and the U.K. This is how they summarized

the state of the helmet art after analyzing the accidents and the damage done to the helmets and the

people: ‘Current designs are too stiff and too resilient, and energy is absorbed efficiently only at values of

HIC [Head Injury Criteria: a measure of G force over time] well above those which are survivable.’ ”

So, in other words, SNELL helmets are designed with an eye towards dealing with impacts where the rider isn’t going to survive in any case, at the expense of doing a better job of dealing with impacts that are survivable. In the case of lower energy, survivable impacts, SNELL helmets don’t do as well as helmets designed with an eye only towards ECE and SHARP.

I suggest that everyone read the cited article.

17 mph ? You guys used to say up to 25 mph. Sounds like the more you learn the less safe a helmet is in that impact.

(not the same Tom, a different Tom)

Having spent a number of years living in Europe, and having been very active in the motorcycling community there, I have to agree with the first Tom’s opinion. Here in the USA we get “my degree is in (blah blah blah”) “I know so and so”, my (ahem) credibility is bigger than your (ahem) credibility how dare you question my expertise, and so on ad nauseum with little in the way of additional reliable and understandable published scientific justification. We beat people into submission in a public venue rather than discuss intelligently from opposing points of view.

In the meantime, the Europeans at least try to come up with something innovative to add more information to the subject at large. If one understood the European research mentality in general one would also understand that there is considerable professional peer review. Is it perfect? No. Nothing ever is. But it is better than the same old same old whose pass/fail one-test-fits-all results are partly tailored with one eye on avoiding releasing sufficient information to support product liability lawsuits in good old litigious USA.

Give the Europeans some credit here. This is good stuff to add to our understanding of a difficult subject filled with a lot of anecdotal BS and outright unsubstantiated personal opinions.

There seems to be a loose correlation to price-performance. Admittedly: there’re some good performing models in the lower prices – there’s a lot of low-rated models while at the higher price ranges: fewer have low ratings.

I applaud the Brits for this. We need something like this on this side of the pond – and replace the antiquated DOT.

this is a job for consumer reports. they’re picky enough to do it and they already buy outright the product/device as a normal methodology. great idea. leave it to the brits to go to that detail.

I contacted Shoei about their US helmets and although they may look the same, they have different shell construction to pass SNELL M2010. Given that the modifications made to pass SNELL are understood to increase helmet stiffness, that would likely result in lower scores under SHARP testing. Personally, I just buy helmets that are ECE and DOT approved. SNELL is just a marketing organization and their science is questionable. Search for “blowing the lid off motorcyclist magazine” for more info.

Snell is geared more towards higher G impacts and double hits, such as what is experienced in high speed racing. In order to achieve this with the same thickness styrofoam core, that core needs to be more dense, therefore G forces transfered to the head are greater in crashes at more normal street speeds.

“Blowing the lid off” is based on the ideas of a couple of graduate students at USC. Snell standards are based on 40 years of research on head injuries. Snell is by no means a marketing organization – the director, Ed Becker, is an MIT trained engineer, and the board of directors is largely medical doctors. Every helmet manufacturer has exactly the same testing equipment as Snell and their “questionable” science. It is plausible that in some low energy collisions you could get a slight concussion with a Snell helmet that you would not get in a non-Snell. It’s even more plausible that in a high energy collision the Snell helmet could save your life compared to the non-Snell. You read a junk science article in a popular magazine and now you have an official opinion. My opinion is based, btw, on my personal relationship with Ed, on my Caltech engineering degree, on my 610,000 miles of motorcycle experience, and on my time spent teaching physics at USC.

Does your engineering degree involve matters that directly relate to helmet efficacy? I have two engineering degrees, and I know almost nothing about the details of helmet functionality as it relates to this type of discussion. I’m also curious how having ridden 610,000 miles, or knowing a guy who knows about helmets makes your opinion any better than any other.

Maybe opening your comments with a jab about ‘junk science’ wasn’t such a good idea here?

I don’t know Ed, but I have ridden a little over 700,000 miles, and I road raced for 6 years. Do I know more about helmets than I think I do? I’m asking because I can’t think of a single example of how any one of my 700,000 miles taught me about how effective a given helmet is when it suffers an impact with a head inside it.

Besides all of this, I’m not sure what all the excitement is about anyway…the current SNELL standard’s shift away from their old ideas about rigidity and towards other standards that require a ‘softer’ helmet is proof that there is validity to past criticism (assuming one trusts the organization’s integrity, and I do).

cliffs: get off your high horse. You are not an expert, and neither is anyone else commenting on this article.

Actually, yah, I spent a fair amount of time studying helmets. My article on helmets, published about eight years ago and updated since http://www.calsci.com/motorcycleinfo/Helmets.html has been read by about 43,000 people. And I stand by my statement: the USC guys, tossed out of the Hurt Institute, and Motorcyclist did a grave disservice to motorcyclists with their junk science.

I read it, and it’s quite informative, as are many other articles on your great site. What I was getting at (and I think if you re-read your post you’ll agree with me) was that you supported your position here with several ridiculous logical fallacies. You have it in you to provide useful feedback, but when you couch it in that rantish last sentence it takes away from anything valuable you have to add.

On an unrelated note, thanks for your web site. It is a treasure.

Well, we can throw out the 610,000 miles as meaningless, I’m not sure why you even included it. Does the fact that the board of directors may not have many (or even any) motorcycle miles under their belts in any way detract from their expertise in the medical realm?

It seems rather telling that SNELL changed their testing with M2010 to bring it more in line with the “junk science” in that article, isn’t it? I know, it was just so that the manufacturers could make helmets that were sold in Europe as well, because that unfortunate ECE spec (which I have no doubt you believe was based on junk science as well) which is in effect there precludes a helmet from passing the SNELL certification. Or that SNELL certification prevents the helmet from passing the ECE spec, however you’d like to look at it. I’m sure the M2010 standard is really a step backwards and results in a helmet that is less-safe than those that met earlier SNELL helmets, right? You can’t have it both ways: it is complete bunk and SNELL is making for safer helmets by adopting the M2010 standard which also brings it more in line with increasing the energy absorbed at lower energy impacts while at the expense of those very high energy impacts you’re so focused on.

Ya…what you said.

A well written piece and some good information

This entire article and the idea behind Sharp is complete crap. Helmets have exactly one purpose: to protect your brain in an accident. There is absolutely no evidence over the last 40 years that any Snell helmet protects better or worse than any other Snell helmet. Stars? Will I get a concussion with a 4-star, and permanent brain damage with a 2-star? What is this, 2nd grade? Helmets are in fact pass/fail: you either get out of the accident without permanent damage or you don’t. I also take strong exception to the swipes at the Snell institute: these guys drove helmet R&D for the last 50 years; without them we’d all be wearing junk helmets.

Helmets have exactly one purpose – that’s BS and calls into question the rest of your comments.

Mark, you just showed how little you know about the Sharp system.

It’s a mighty fine system because it’s ratings in any given impact area are based upon how many Gs are transfered to the area of the head. In other words, if 6 Gs are directed at the helmet and 3 Gs are passed onto the head, that’s a rating of X. If 6 Gs are directed at a different helmet and only 2 Gs are passed onto the head, it gets a better rating. Things like this make the difference in rating the effectiveness of a helmet. SHARP also accounts for other features such as strap retention, flip up chin bar engagement, venting, visibility and more. It’s a good selection tool.

Simply noting wether a shell cracked or not upon impact then applying a DOT or Snell sticker to the uncracked helmet is next to worthless. This just determines if a helmet meets “minimum” safety standards based on minimal testing procedures. SHARP actually rates a helmet based on more tests that seem to be more realistic in nature, then it measures it’s performance on a scale so we all can see which is better or worse in any given area.

Actually, more typical numbers would be 635 Gs directed at the helmet, and 320 Gs passed onto the brain for a duration of perhaps 1.3 milleseconds. This is what a Snell test report looks like.

Snell rigorously tests strap retention. Snell does not currently test flip up chin bar engagement because only one flip-open helmet has ever been submitted to them for testing, and that helmet is not marketed in the US. Snell tests peripheral vision.

Tell me a time and come by my shop. I’ll be happy to arrange a tour of the Snell facilities for you and you can see for yourself first hand what a “marketing orgainzation” with “worthless” tests does.

There’re some features related to safety that you can see with a plain eye. Fashionable features such as wings, spoilers, etc. are potential hazzards that could stop the helmet from sliding and snag on ground thus directing dangerous forces to your neck. MX visors are useful while riding but can be dangerous if mounted too well, they should have break-away plastic screws, not heavy-duty metal ones.

ECE 22.05, which is also known as Regulation No 22, have requirements (starts at 6.6) on attachments to the helmet that reflect that they should easily shear off to prevent just that. I’m pretty sure SNELL, for all its faults, evaluates that as well. I’m not sure about DOT.

As usual, the Euros are more intelligent when it comes to all things moto-dom.

Then why do Asian brands dominate globally?

Not talking about who sells the most bikes. I’m talking about about how Euros approach motorcycling in a more intelligent manner. Ie: motorcycling in Europe is a way of life instead of it being a lifestyle like in the USA.

MC/scooter riding has been a way of life for me for over 48 years. I spend more time on them by far than any other mode of transportation.

Sounds like you are the exception and not the rule when it comes to a USA rider.