Let’s face it. There are motorcycle manufacturers out there that consistently draw among the most fanatical, and devoted, customers despite producing machines that employ older technology (such as air-cooled, two-valve engines). The devotion, and passion, shown by owners of these particular marques’ machines results from a combination of function and largely intangible elements. These motorcyclists are receiving something of tremendous value to them totally unrelated to quarter mile times, stopping distances, ultimate cornering ability, etc. What these people get from their bikes is very real to them, nevertheless, and very satisfying. It is not just about style, either. The simplicity of the technology is part of the attraction.

It may seem silly to attempt to explain what is happening here, but I can’t resist. Bear with me while I take a short side trip that I will try to tie back into my discussion about this Moto Guzzi, and motorcycles like it.

During a time in my life when I was particularly interested in Zen, I read a book called “Zen and Japanese Culture” (this was in the late 1980s). Written by Daisetz T. Suzuki (who died in 1966 at the age of 95, and deserves a much more extensive introduction), this book has an interesting discussion about Japanese art and, more importantly for our purposes, the perception of beauty, or the quality of attractiveness. I won’t bore you with extensive discussion of the Japanese traditional concepts of wabi (poverty or simplicity), sabi (rustic unpretentiousness or archaic imperfection) or the use of asymmetry by Japanese artists and architects, but contemplate these statements by Suzuki for a minute:

However “civilized,” however much brought up in an artificially contrived environment, we all seem to have an innate longing for primitive simplicity, close to the natural state of living. Hence the city people’s pleasure in summer camping in the woods or traveling in the desert or opening up an unbeaten track. We wish to go back once in a while to the bosom of Nature and feel her pulsation directly . . ..

[Regarding the economy and asymmetry of Japanese art,] where you would ordinarily expect a line or a mass or a balancing element, you miss it, and yet this very thing awakens in you an unexpected feeling of pleasure. In spite of shortcomings or deficiencies that no doubt are apparent, you do not feel them so; indeed, this imperfection itself becomes a form of perfection.

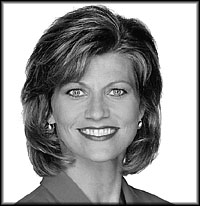

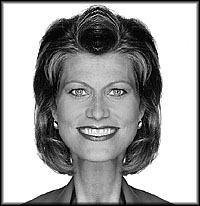

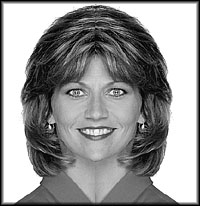

We can all participate in a simple exercise when we look at perfectly symmetrical human faces versus the asymmetrical faces presented to us by nature (the left half and right half of any individual’s face is different — they are never a perfect mirror of the other). It turns out that perfect symmetry makes a face, generally speaking, unattractive. I will let the pictures, and their captions, illustrate this point to you.

|

|

|

|

Face 1

|

Face 2

|

Face 3

|

The asymmetric face of Cindy

Crawford, including her famous mole, is attractive. |

Moving a bit closer to the subject at hand, it occurred to me a couple of years ago that adding a kick starter to any motorcycle (that’s right, any motorcycle) might have the effect of creating a closer bond between the motorcyclist and his machine. The thought came to me when one of my readers sent me an email regarding his ownership experience with Kawasaki’s retro W650. The W650 (no longer sold here in the United States) featured both push button electric starting and a kick starter. This reader (who had owned, and continued to own, modern motorcycles, including Yamaha’s R1) told me that he enjoyed using the kick starter, because it bonded him with the machine, and made the experience more enjoyable (I wish I could find that old email, because his words were far better than mine at describing this experience). All of us have observed that human beings are generally attracted to other beings that are young, and, as a consequence, simple, vulnerable and in need of assistance. Human babies attract us, and, in a different, but similar way at the same time, young animals (puppies, for instance) attract us. While the push button, electric starter is more efficient, and the kick starter comparatively crude, feeling that the W650 needed his physical assistance coming to “life” was pleasurable.

It’s a good thing Lyle is a

nice guy with a great voice |

Of course, like everything else, these concepts of asymmetry, simplicity and archaic imperfection have their limits. If something is too asymmetric, for instance (take a look at Lyle Lovett’s face — one only a mother, or, apparently, Julia Roberts, could love), it becomes unattractive, again, or even annoying. The same thing occurs if something is too imperfect, or dysfunctional. So, a certain amount of balance is necessary.

The irony of this discussion is the use of Zen and Japanese Culture to illustrate the attractiveness of imperfect, even flawed, “machines”, while it is the Japanese who have most often been accused of “sanitizing” motorcycles and automobiles to the point of making them seem bland. Several years ago, the Honda Accord automobile was almost synonymous among automobile journalists with the concepts of “perfection” and “blandness”. More recently, Honda and Toyota now talk about the “emotion” they have put back into the Accord and the Camry.

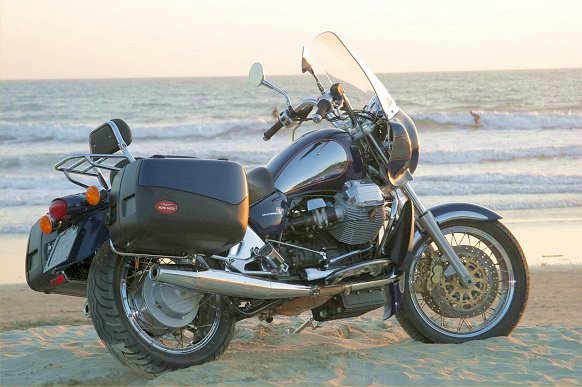

So, what does all this have to do with our evaluation of Moto Guzzi’s 2003 California EV Touring motorcycle? The EV Touring isn’t going to set any records for mechanical perfection or objective motorcycle performance, but it has a certain attractiveness or charm that stems from its design and performance, nonetheless. It is also a machine that has a devoted, and even fanatical, following. Many Moto Guzzi riders (like Harley-Davidson riders, for instance) will never ride anything else, and they will be the first ones to tell you they won’t ride anything else.

When Aprilia bought Moto Guzzi a few years ago, Ivano Beggio (head of Aprilia) promised to invest huge sums of money into Moto Guzzi in order to bring this great Italian marque up to the level it deserved, both in terms of manufacturing quality and design. The 2003 California EV reflects some of the recent changes brought by Aprilia to a machine that, in its fundamental nature, has been around for a long time.

Most notable is the addition of hydraulic valves, making the California EV even more reliable — the California EV, like other air-cooled, two-valve Guzzis, is already known for its reliability. The EV Touring model we tested comes with plenty of conveniences for the long distance traveler, as well, including 12 volt accessory plug (for heated clothing and other accessories), heated hand grips, color-matched hard saddlebags, generous upper fairing and lowers (to keep your legs warm), and a broad, touring seat with passenger back-rest and luggage rack.

The brakes operate in a linked fashion (more about that later) and feature two 320 mm discs up front gripped by Brembo four-piston calipers, and a single 282 mm disc in the back gripped by a Brembo two-piston caliper.

The basic design of the California EV is that of a cruiser. Extremely low seat height (for a tourer) with a “feet forward” floorboard set-up, while the bars curve back to the rider, leaving him/her in an upright position. Tires are somewhat odd in size, including 110/90/18 front, and 150/80/17 rear tubeless radials mounted on spoked rims. The California EV Touring weighs in at a claimed 573 pounds dry, and carries exactly 5 gallons of fuel.

The California EV Touring features a version of Moto Guzzi’s proven, air-cooled 1,064 cc v-twin engine mounted traditionally across the frame. The engine puts out a claimed 74 horsepower at 6,400 rpm and 70 foot pounds of torque at 5,000 rpm (at the crank). The power is fed through shaft drive to the rear wheel.

45 mm forks grace the front end of this machine, and they are adjustable for both compression and rebound damping. The rear suspension features dual hydraulic shocks adjustable for rebound damping only.

The transmission is a five-speed affair, with relatively close spacing between the gear ratios.

This Moto Guzzi is not your typical cruiser (indeed, there is very little that is “typical” about any Moto Guzzi). When a similar machine won Cycle World’s huge cruiser shoot-out several years ago, it certainly surprised a number of people. As Cycle World noted, these bikes handle quite well (the beefy 45 mm fork mentioned above not only features compression and rebound adjustability, it comes standard with a fork brace). Engine performance is also towards the performance end of the “cruiser class” (although that is changing with the continual increase in the displacement, and performance, of cruisers in general).

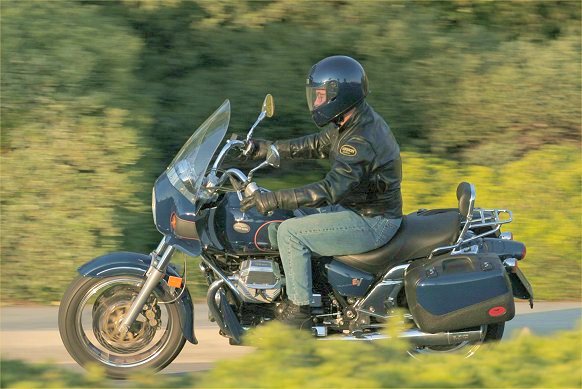

After adjusting the suspension to our liking (we made a huge change in the fork settings, compared to the prior tester — ending up with 7 clicks out on the right fork, the rebound damping adjustment, and 4 clicks out on the left fork, the compression damping adjustment) the EV Touring did handle well — changing direction quickly (partly, thanks to those narrow tires), and felt stable up to about 100 mph. Although the engine seemed to vibrate more than the last air-cooled Moto Guzzi I rode (in 1999), vibration is generally not a problem for the rider. The seat keeps vibration off your butt, and the gel-mounted floorboards keep the vibration from bothering your feet. The vibration did occasionally become an annoyance at the handlebar grips when cruising in fifth gear on the freeway above 80 mph, or so.

That vibration at higher rpm levels reflects the fact that this particular Guzzi likes to be short-shifted, rather than revved. The machine makes good, pleasing torque down low, and Moto Guzzi seems to have their stock fuel injection settings fairly well sorted out (that has not always been the case). Acceleration is strong, but nothing to write home about if you are used to riding sport bikes, or even powerful sport tourers. My guess is the bike would turn mid-13s in the quarter mile.

The big, two-valve, v-twin shrugs off the added burden of a passenger and luggage — seeming to accelerate with the same vigor. Speaking of passengers, every one of ours praised the seating position, and loved the built-in back rest.

Rider ergonomics are reasonably comfortable, as well. The short seat height of the cruiser design does place your knees a bit higher than they would be on tourers from other categories, but not much different from other tourers within the cruiser category. The bolt-upright seating position is comfortable for longer trips, as is the broad, but firm saddle.

Wind protection is quite good, and the lowers protecting your legs were well appreciated while riding through the unseasonably cool weather here in California this Spring.

As a dedicated tourer, this bike is good, but not great. The aforementioned handlebar vibration, the relatively short gearing (a sixth gear, or an overdrive fifth, would be appreciated), and the limited range of the 5 gallon gas tank are not as well suited to this task as they could be. Nevertheless, the bike is clearly more comfortable than most for moderately long trips — particularly, if you keep freeway speeds below 80 mph.

The stock luggage (manufactured in Germany) is excellent. Well designed, easily removed/installed, and relatively large (although, a large, full-face helmet barely fits inside), color-matched bags like these are a great feature on a stock motorcycle.

If you like longer tours, the bike will accept a top case, as well, and the heated hand grips are a welcome companion when riding at night or in the cold.

The linked brakes work well if you know how to use them. Using the front brake alone, you will not find the braking force you need, or want, in a panic situation. You need to teach yourself to use the rear brake in tandem with the front (they are linked, remember?). Using the rear brake requires a special technique, however.

In order to use the rear brake, you must lift your foot off the floor board and place your heel on a small stub extending from the frame. After placing your heel thusly, you may depress the rear brake pedal. This process was puzzling, and annoying, for the first several hundred miles, but actually began to become somewhat intuitive with extended saddle time. I have heard of Moto Guzzi owners modifying this set up, so that the rear brake pedal can be applied in a more conventional manner (with your heel on the floor board).

When the front and rear brake are used together, they are extremely powerful, and haul the bike down quickly and controllably. Basically, they do what you would expect from triple discs and Brembo calipers.

The five-speed transmission shifts somewhat reluctantly (and the occasional missed shift is inevitable — use plenty of boot power). Some of Moto Guzzi’s other models have received an updated six-speed transmission, and the California models would greatly benefit from a similar upgrade (perhaps, next year?).

The look of the Moto Guzzi California EV Touring is clearly European, and out of the ordinary here in the United States (you don’t see very many Moto Guzzis here). The finish on our test bike was good, although, perhaps not quite up to Japanese standards. Everything seemed to function properly on the bike, but we did have to adjust the clutch after just a few hundred miles.

The Moto Guzzi has all that intangible stuff we talked about earlier . . . in spades. The noise and vibration of the machine make you feel you understand exactly what it is going through. The extra effort necessary to ride a Guzzi is, in a certain way, pleasing, as well. There is nothing “sanitized” or “bland” about a Moto Guzzi California EV Touring bike. To the contrary, it is a spicy Latin with some primitive, even puzzling, design elements. It may annoy you at first (it may annoy some of you, forever), but it will grow on plenty of you, over time.

Moto Guzzi riders don’t often travel in packs of Moto Guzzis. They are often alone, with no one to show off to and no one to dress up for. They simply love their “imperfect” machines. I think I understand why.

Visit Moto Guzzi’s web site for additional information and specifications.