As a die-hard motorcycle fanatic, professional motorcycle mechanic and experienced road racer, I couldn’t have been more excited when Dirck asked me to attend the world press launch of the GSX-R750 at Suzuki’s test site near Hamamatsu, Japan. Having raced two-stroke GP bikes here in the United States for a number of years, and even dabbled in four-stroke supersport competition (I raced four of the AMA Supersport rounds in 2003 aboard a Yamaha R6), I certainly understood the heritage of the Suzuki GSX-R750, and anticipated an interesting experience testing Suzuki’s new flagship.

My first miles on the GSX-R were when I was about 7th or 8th in queue behind a Suzuki Factory Test Rider, being lead around Suzuki’s Ryuyo Proving Ground. This was one of the few occasions that I could actually ride the bike relatively slowly. My initial thoughts? The GSX-R looks like a 600, feels like a 600, turns like a 600, and rockets forward like a 1000.

The flowing nature of this track suited the bike perfectly, including the intimidating 1.25 mile straight. Once in 6th gear on Ryuyo’s back straight, I was holding the throttle full stop for 16 seconds. That was enough for an indicated 300kph (the equivalent of 186mph). Even if the speedo was 10% fast, that was close to 170mph for at least 10 of those seconds. I have done some pretty extreme things on motorcycles in my years, but this seemed pretty hairy.

As the test rider clicked off more laps, upping the speed gradually, we were able to stretch the throttle cable more and more on this extreme length of blacktop. Eventually, he pulled aside and we were able to circulate on our own. I cannot stress enough how much this bike behaves like a 600cc machine when stopping and turning. The beast it turns into when accelerating is nothing like a 600, however. Turn-in is crisp, and it flicks back and forth with ease. When the throttle is applied though, it feels like you are at the business end of God’s own Louisville Slugger.

This much power would not be of much use without being able to get it to the ground. The traction on the Suzuki was fantastic. Not only were the Bridgestone BT-014’s great, but the chassis dug in and allowed the bike to shoot forward, not sideways, and for the most part not upwards. I am not a wheelie guy and appreciate a bike that likes to stay planted when properly ridden. I was quickly comfortable on this machine, feeling that I could take it to 8/10ths of my capability almost immediately. Thankfully, this allowed me to acclimate to the high speeds common on this track.

The back straightaway was remarkable, but I should go through a quick lap around the whole Ryuyo Proving Ground to properly explain the way this bike was tested. There are not many people that have circulated this track; there is not much data about it readily available. Back in the mid-seventies, legendary racer Gary Nixon was riding an RG 500 at this facility when it seized. He suffered serious injuries and I can see how easily that could have happened here. On the shorter front straight, you pass the pit area, just clicking into 6th gear and bend slightly for a left-hander kink, then to a small straight. As you approach the end of the straight you are topped out in 6th, then shift down 2 gears and touch the front brake for a right-hander sweeper that has a beautiful flowing line. After that is a small straight that allows you to rev out 4th, then snick a downshift into 3rd for my personal favorite corner, a left-hander bend that starts the “S” section. The track is 3 lanes wide in this area, with small white marks indicating lanes at 1/3rd and 2/3rd’s track. It is very easy to navigate and obtain the proper, or at least consistent, line due to these lanes.

That sweet left-hander turns into a right-hander and back into a left-hander, which ends up on a short chute. I would take that whole section in 3rd, accelerating to redline at the end of the short chute. That puts the bike into a near perfect 230ft-radius turn, which then dumps out onto the unbelievably long back straight I have already described. The track is surrounded by large walls and some shrubbery, with what looked like wrestling mat placed in some areas. I would get into 2nd before this corner, and since it leads to the long straight it is imperative to get a decent drive. High siding here would mean much carnage for both man and machine and kept all journalists, including myself, humble and careful.

At the end of the back straight is a huge right-hander sweeper, with a 650 foot radius. We were all extremely careful in this corner as it was taken flat out in 4th and would not have been a friendly place to lose control. The end of that results in the slowest corner on the circuit, a right-hander hairpin taken in 2nd. Accelerating out of this corner was great fun, and it puts you into a long left-hander sweeper that dumps the bike back out onto the front straight.

So, it is a wide fast track, with a great flow, but an extreme amount of danger due to immovable objects and high speeds. As I circulated it more and more I felt like I was getting tremendous insight as to how a good portion of Suzuki’s product line had been developed, especially the GSX-R line. The GSX-R750 just loved this facility, never faltering during any of the sequences. Given that back straight, however, I can imagine this is still the domain of the Hayabusa.

The new GSX-R750 really made my pulse quicken. Out of the slower corners, pouring on the throttle at about 7k, the machine would smoothly build rpm in a manageable way. But if I happened to be a gear lower at 10k, then applied the same amount of throttle, it would really get mean and want to break out the rear or lift the front depending on how leaned over I was. I only got the rear wheel sideways a couple of times. I was being as careful as I could. If I did crash I would most likely be hurt (not to mention embarrassed).

It was determined by some of the other wilder, and more seasoned, journalists that this bike is very easy to wheelie when provoked. I know nothing of wheelies, not yet anyway. I had a bad experience with a VTR 250, hot asphalt and a dumped clutch at 11k when I was 16 (that I have still not fully recovered from).

At the intro with us were the Vesrah Endurance Team members that won the WERA Championship this past year. One of these racers is named Tray Batey. He is a 42-year-old racer for hire that has one of the most respectable records in United States Roadracing. He is fast and consistent. At one point in time on our first day, he, the other two WERA Champion racers (Mark Junge and John Jacobi), and the omnipotent Kevin Schwantz were doing hot laps on the new 750, entertaining all of the Suzuki workers and about 30 journalists. They were really cooking coming out of the last corner on the track onto the front straight. More than once Tray would be in a wheelie, coming in front of the pits, keeping up with the rest of them doing at least 120mph. His throttle control was amazing. On the back straight, which also runs in full view of the pits, he would be doing a stand-up wheelie, still tucked behind the bubble! Since the rest of his group was still in a full tuck and definitely not holding back, we in the pits surmised that he must have been doing at least 140mph. It was impressive, but not nearly as impressive as watching him land it when it would finally start to wobble!

The only aspect of the bike more extreme than the power is the brakes. The new-for-2004 radial Tokico’s were superb. The master cylinder is now of a radial design, as well, with a larger-bore piston. The strength of the caliper allowed Suzuki to not only make the brake rotors smaller in diameter, but a little bit thicker (and they still weigh less!). The bike ends up having strong brakes, solid progressive lever feel and the lowered inertia of smaller brake rotors and less unsprung weight. This is not the reason that this bike handles so well, but it is a contributing factor.

Hitting the brakes while downshifting for one of the fast sweepers, it would easily want to yank the rear wheel off of the ground, and it felt good doing it. Downshifting into one of the slower hairpins, I could modulate the brakes as I needed. I like it when the front brakes give me good feel as I am letting off of them, which helps for trail braking. Due to my GP bike experience, I tend to trail brake very hard, all the way up to the apex of any given corner, and it has bitten me on these heavy (relative to a GP bike) four strokes. I did try as much as possible to get my braking done before I turned in, but trail braking is a hard habit to break, and more than once I found myself doing it, and the 2004 GSX-R750 didn’t mind it, at all.

The rear brake is now connected directly to the swingarm, instead of to the unsightly/heavy brake torque arm. The rear master cylinder bore is larger. The rear brake works very well, and while the braking force is now sent into the swingarm (instead of to the frame, as with the torque arm), I am sure it is not to the detriment of the machine. I would use it going into one particular corner where I wanted to trail brake, but not risk losing the front. It helped tighten up the line, and in some cases would get me out of trouble.

The front forks are redesigned to accommodate bottom mounts for the radial brakes. As I did more sessions, I gradually added damping to the forks. I found that an additional 1/2 turn on the rebound and 1/4 turn on compression worked well at this circuit. I started with 1/4 turn on the rebound, but under braking I was getting a wicked chatter that was forcing me to let off the brakes and run wide. So another 1/4 turn of rebound, and winding the spring preload down one line, did the trick. As with most stock bikes, the valving would have to be modified to truly make the front end feel good at 10/10ths, but with that said the stock set-up was nevertheless impressive

I never touched the rear suspension. It never bucked or wallowed around on me. I was trying not to be too heavy with the throttle on corner exits. This was my first press introduction, and I did not want to risk my reputation so early in the game! I did get the rear to step out on a couple of occasions, but that was mainly due to me yanking too hard on the throttle too early with the bike leaned too far over. The rear suspension has 130 mm of travel, which might help explain the substantial rear grip and the ability to make nearly 130 wheel horsepower turn into forward motion.

The swingarm is new, but the same length, width and height as last year. The rake (caster angle) of the front forks is down .75 degrees to 23.25, and the trail is 93mm instead of 96mm. These seemingly aggressive specifications are surprising considering the characteristics of the bike. I could not manage to get a tank-slapper out of it, even during those few ham-fisted corner exits. It would wobble one or two times and come back to center, stable as a steel table. It does have a steering damper stock.

During the second day of our testing, the winds that this region is famous for kicked up proper. I am used to riding at Willow Springs (another notoriously windy track), so that did not bother me too much, but it was a genuine 30-40mph cross wind hitting the straightaway in a perpendicular fashion. It would move the bike back and forth a few feet. Yes, I had slowed down quite a bit due to this, but I was still going at least 160mph, and the steering would track straight and true during the worst of it. What was intense was this wind going into the corner after the long back straight, which is much like the infamous Turn 8 at Willow Springs. The bike was so stable that I was able to make some serious corrections mid-corner when an errant cross-wind would hit me.

What looks like a recipe for a twitchy, unstable machine on paper ends up being quite a well-mannered sport bike with fantastic steering and handling characteristics. As I mentioned earlier, initial turn-in is great, both hard on the brakes and coasting, and mid-corner feel is solid (I could feel either end working for me at any given time).

The frame is quite a bit different from the ’03 model. It is now made of extruded side beams, instead of welded-together stampings. The extrusions actually have a reinforcing rib internally, much like what was first seen on the Honda RC30 16 years ago. The dimensions of these side beams are thinner and taller than the ’03 model. The steering head and swingarm pivot plate sections are cast aluminum and welded to these extrusions. This is another example of a trend towards taller and thinner frames and swingarms. One can only hypothesize that the manufacturers are now starting to put a lot of credit in having a frame that acts as the suspension when the bike is fully leaned over, and the suspension itself has stopped working efficiently.

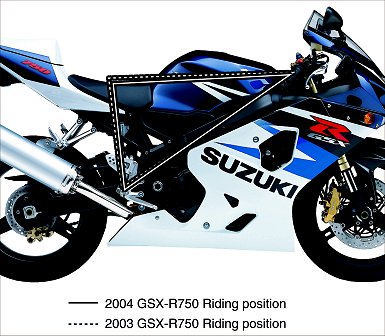

One of the reasons that I acclimated to this machine so quickly is the new, small dimension it has. GSX-Rs, by and large, have never been comfortable for me to ride or go fast on. They always seemed too wide, especially at the gas tank, and generally cumbersome to move around on. The new 750 is quite a changed machine. The fuel tank is narrower at the knee grip point, which is a huge step. This was achieved by restructuring the throttle bodies and airbox to tuck in closer to the centerline of the machine. The main frame is narrower between the spars, the distance between the left and right swingarm pivot section is narrower and the distance between the footpegs is narrower than the ’03. This makes a big difference for someone that has cut his teeth on 125cc roadrace machines and ultra-thin Ducati twins. The bike is still pretty wide for my tastes, but now it is not a hindrance.

I did not notice it until I had done a few sessions on the bike, but the footpeg-to-seat relationship is closer than I would prefer. After I got off the bike after 20 minutes, I would have to stretch and massage my legs. I am 5′ 10″ tall and weigh 150lbs, so I am really skinny, but average height. This seat-to-pegs relationship is only a little less than the ’03; I do not like it, and would want to have a taller seat. This might be acceptable in race situations, but on the street it would tax my legs too much.

The big story about this bike is how close it is to the size and handling of a modern 600, but the engine updates should not take a back seat to this down-sizing. Many measures were taken to improve the output of the GSX-R750 and, much to my delight, the bulk of this was in lightening circulating and reciprocating parts. The 750 and its little brother (the 600) now sport titanium valves. The lightweight valves allow lighter valve spring rates. Couple this with lighter cams, and you have a 500rpm higher redline and engine response that gets to that redline quicker than the ’03.

The pistons are a tad lighter. The crankshaft and rod weights are unchanged. There are now ventilation holes at the bottoms of the cylinders that effectively make the whole crankcase a single chamber, virtually eliminating the pumping effects of pressure at the bottoms of the pistons. Suzuki claims a 2% increase in torque output at high rpm due to this.

The engine compression ratio is higher due to smaller combustion chambers. The exhaust port exit diameters are bigger than the ’03. The intake cam has more lift and longer duration. All of these small changes add up to a 5% increase in horsepower for ’04, and I can attest that this machine sits up and barks with the best of them. Not only is it more powerful, but (due to the lightweight moving parts) it responds quicker to the throttle. A couple of changes to the electrical system and fuel injection have netted a more refined fuel map and ignition map (read: EPA Friendly but still hell for fast).

Overall, the engine is excellent, providing smooth, linear power with no hiccups or flat spots. The bike smooths out above idle. Once underway, I noticed a sweet note from both the intake and exhaust, and very little vibration at either the bars or pegs. This perception might change with a good street ride, though.

More power means more heat, which Suzuki addressed with a larger capacity oil cooler and a much bigger radiator. The radiator is no longer a curved rectangle, but a large curved trapezoid that dips deeper than on the previous generation. It is quite impressive to look at. It is amazing to see things once reserved for factory superbikes now showing up on production bikes. The cooling fan is smaller and lighter, but more efficient.

Weight savings did not stop at the engine internals. The cylinder head bolts and cam housing bolts are lighter, the oil line feeding the cam chain tensioner is now internal, the muffler now has some titanium parts, and even components like the blinkers, computer and throttle bodies are now lighter. All of the individual weight savings may sound insignificant, but when building a race bike, believe me grams are worth a lot. All together, the ’04 GSX-R750 is 6 pounds lighter than the ’03.

I did have trouble with clutchless upshifts in the higher gears. At no point in time did my bike let me shift from 5th to 6th without completely backing out of the throttle and using the clutch. Even with the 4th to 5th upshift I had to be very determined. The rest of the gears had no problem with clutchless upshifts, while still partially on the throttle.

I was using street pattern shift on the first day of testing, and due to this problem I decided that it must be me and that I should revert to my usual upside-down racing shift pattern. The bike was much nicer for me to ride after that change, simply because I am more comfortable with it that way, but it did not do one thing for the shifting. Another journalist said he had the same trouble, but assumed it was either a pre-production problem, or the fact that the bikes were not being completely run-in.

Otherwise, the transmission was good, with new closer ratios and what seemed to be a fine final drive. At Ryuyo, an even taller final drive would have been just dandy. The lower gears were like butter to get in and out of, with a perfect lever feel.

The throttle was very soft, as if the spring you are working against to keep the throttle open is just not tight enough. That is a matter of personal preference, but I do not like a throttle that moves when I am in the middle of a corner and hit a bump. A stiffer spring would be better.

The switchgear and instrument cluster are great, and (aside from the short seat-to-peg distance) I had no issue with the ergonomic aspects of the cockpit. One of the features of this cockpit is an Engine Rpm Indicator, or “shiftlight”, as I would call it. I did not use this feature, as I find it to be a distraction, but for those of you who like to know when to shift, you are now in “Gixxer” Heaven.

As I would put my legs down at a stop, my knees would hit against the backside of the side fairings. It was an annoying problem, but certainly not something that would keep me from recommending the bike. Another tester who was a few inches shorter did not have that problem at all.

I really like the styling and graphics of this new GSX-R750. I love the way Suzuki treated the vertically stacked headlamps, giving them some beautiful triangular shapes and retaining a family heritage. Overall, the bike looks so small. It is sharp, exciting, mean, flashy and retains its boy-racer style, but holds its own as a timeless design. The new LED taillights look right, too. The black frame will alienate those people who love to polish their frames, but I would not say that is a bad thing. The black of the frame components adds to the small look of the bike. The lines are tight, from front to back, and the cherry on the top is the use of the traditional Suzuki “S” on the gas tank. That is high style, and a trend I hope they continue.

You may be wondering why a 750cc sportbike is needed in this era of 600/1000 inline fours. A bike with the fortitude and heritage of the GSX-R750 is not going to be taken off the market, unless it does not sell, and they definitely will sell. The venerable “Gixxer” has always been the 750, since its inception in 1985. There is a huge market for them on name alone.

This 2004 GSX-R750 will sell for another reason. The modern 1000s are too much motorcycle for most mortals. They generally scare their owners on a daily basis. And while that power is intoxicating, and somewhat useful in the right hands, you are still dealing with quite a large rotating mass and a bike that is set-up for high speed. The 600s, on the other hand, are set up to handle really well in any condition, but their engines do their best while screaming at high rpm. Most riders would love to have the sweet, lithe handling of a 600, but the grunt and sheer power of a 1000. And that target lies squarely on the sharply styled GSX-R750. So Suzuki presents us with a new 2004 GSX-R750 that truly offers the size and handling capability of a 600, with a fully developed 750cc engine that, in the real world, gives away very little to the 1000s. The nits I have picked about this machine would not prevent me from heartily recommending it to sport riders. I would gladly own this bike, and would be proud to have it sitting next to my other motorcycles. I look forward to seeing what this thing is like off of the racetrack, and how it stacks up to the latest 1000cc machines.

The U.S. MSRP for the 2004 Suzuki GSX-R750 is $9,599. Take a look at Suzuki’s web site for further details and specifications.