Like most people, motorcyclists tend to have an opinion on everything, and particularly on what the perfect motorcycle should be. We think we know exactly what we want from our ride, and we usually spend the majority of our riding careers trying to find that perfect bike, or modifying the imperfect machine we own. But only those CAD-CAMing gurus in their spotless design studios in Japan and Europe can take dreams and turn them into functioning motorcycles, right?

Forty-eight year old Jay Abington doesn’t see it that way at all. Inventor, mechanic, rider, he’s the kind of do-it-all guy Thomas Jefferson had in mind when he envisioned America as a place where the yeoman farmer could live and thrive, dependent on nobody but himself. When Jay sees a problem, he solves it pro per: “I don’t have boundaries to what I like to do; I do it all.” He’s worked on and tinkered with “everything from high-speed zip lines to eight-second go karts.” He’s built a lot of weird things, including the “aqua launcher,” an aluminum-framed person launcher designed and built by Jay for a friend so he could shoot a 200-pound man off the roof of a houseboat (he didn’t explain why he needed to shoot a 200-pound man off the roof of a houseboat). When Jay mentioned that he “didn’t get very far with the jet engines before the divorce hit,” I decided not to pry.

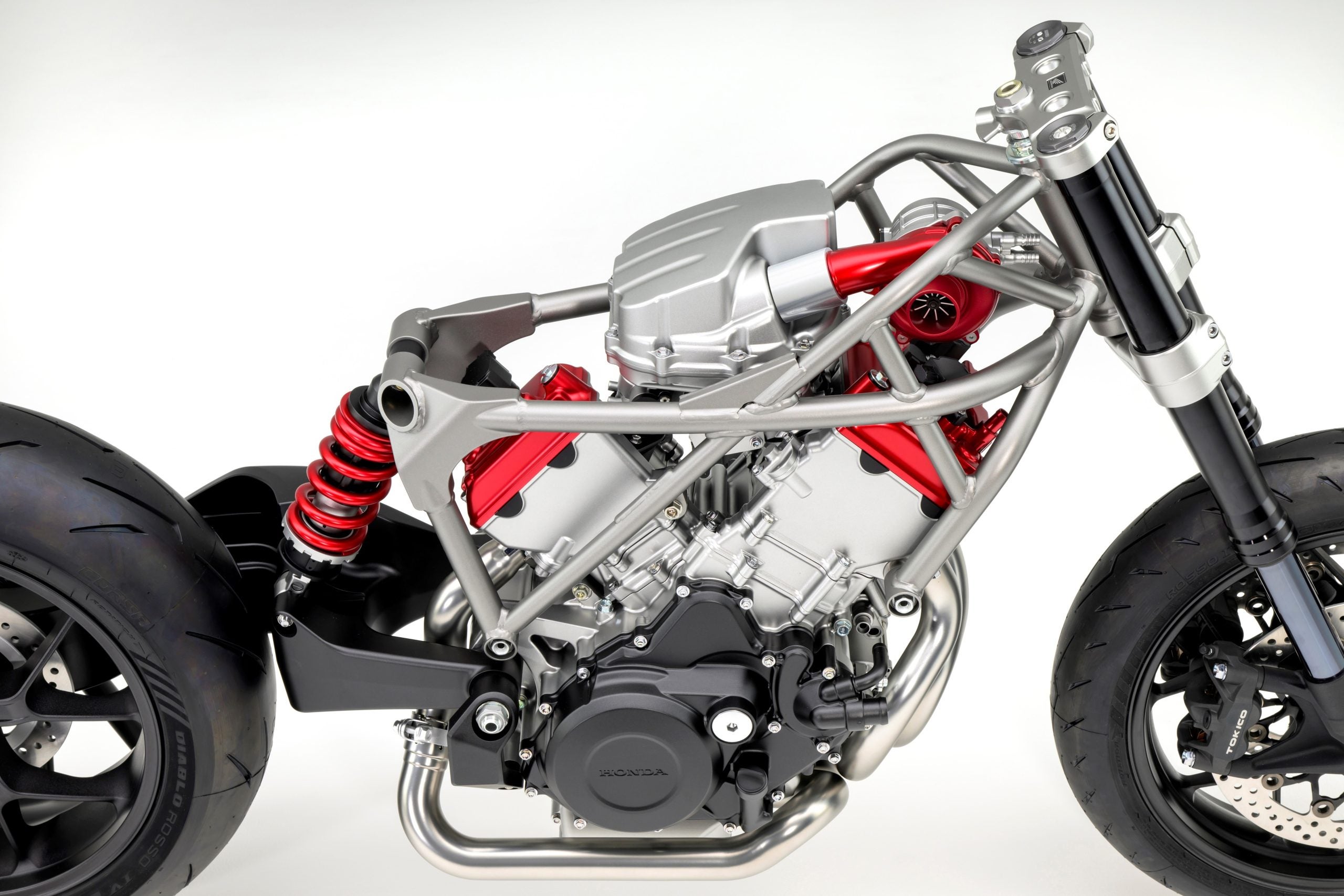

So when Jay figured it was finally time to get his dream bike, he wasn’t about to go to a motorcycle shop to buy it. Inspired by Gary Nixon’s Kawasaki Triple flat-track bike he watched decades ago at the San Jose Mile, he looked for a ’70s Kawasaki two-stroke 500cc Triple. He found a complete ’76 KH500 in Grass Valley, but there was no way he’d be satisfied with the stock frame, a frame that wasn’t considered competent 35 years ago. But that was no problem: Jay worked at BMW race-bike builder CC Products in the 1980s, where he added to his already full portfolio of skills garnered from working in automotive and motorcycle shops since High School. “I wanted to put everything I know into alleviating everything I didn’t like from a motorcycle.” He wanted a frame that was rigid, lightweight and easy to take apart/reassemble, so he put his pipe-bender to work on thin-wall 1.25-inch chrome-moly tubing, to pretzel into a design inspired by Erv Kanemoto’s KR750 that Nixon (Gary, not Richard) raced in the global 750 GP class in 1976. Jay is all about the thin-wall, large-diameter tubing, which strays from the norm of thick-wall, narrow-diameter tubing, but provides better rigidity and less weight.

The resulting chassis is a wondrous thing. It weighs just 22 pounds, including the motor mounts and swingarm, and Jay can do a motor swap in 30 minutes, or have the whole bike apart in an hour. The belly pan doubles as a fuel tank, and an incredible set of expansion chambers bulges out above the motor. The exhausts end in a Gatling-gun like array jutting menacingly out behind the bike at belly level. Wheels, brakes and swingarm are from a cannibalized ZX-9. Gassed up it weighs just 310 pounds.

Jay’s intense focus allowed him to build the bike in just three months, and most of that time was spent tuning the engine. I asked him how he stays focused on his projects. “I have to make sure I’m spending time regularly or I’ll lose interest.” That led him to make a set of rules: “Spend a certain amount of time per day, you gotta force yourself through it. Don’t do stuff that’s been done. Don’t be afraid to waste material…if you don’t like it, scrap it and start over. And picking your project is the most important rule of all; you don’t have a ton of time in life, so make it count.”

I noted that the biggest fabrication project I ever embarked on was to make a license-plate bracket out of an old piece of Triumph muffler. Jay laughed and said, “guys will settle with what they’re capable of doing, but not me. If I don’t have the skill or the tool, I’ll go out and get it. I never say I can’t do something. I’m not a big shop, and it’s inspiring to guys: they figure if he can do it I can do it.”

Jay grew up tearing around the Santa Cruz mountains, riding his pull-start minibike to school with his friends. At 16, he was building three engines a week, and when his father took him to Erv Kanemoto’s shop to pick up a motorcycle Erv built for Jay’s dad, he went crazy for motos. “I’ll never forget the sight of thousands of two-stroke pipes hanging from the ceiling” of Erv’s shop in San Jose, Jay recalls. And then “out of a shed pops Erv, Gary Nixon and Kenny Roberts.” No wonder Jay’s devoted his life to making things lighter, faster and more fun.

Now he gets to ride around on what is the “funnest” bike he’s ever piloted (he says it’s more fun than driving a bulldozer through a house, which is saying something), crafted entirely by his own hands from a concept he created. Jay is always looking for another project: email us and we’ll put you in touch with him. It’s what he loves: “It’s all I do. I’ve suffered in some departments, but it’s worth it. I’m a gear head, 100 percent.”