There is an old, tired phrase: “That’s a tough act to follow”. They said it when coach John Wooden retired from the UCLA basketball program. They said it when Michael Jordan retired from professional basketball (the first time . . . remember?). They said it when Pele retired from soccer. In these instances, of course, it was a very appropriate thing to say.

You don’t really expect to follow a Wooden, Jordan, or Pele with a replacement that shines just as brilliantly. At best, you hope that the replacement doesn’t pale too badly by comparison. Often, of course, it does. When Ducati introduced the 916 superbike in 1993, its physical beauty was immediately apparent. Designer Massimo Tamburini had created a stunning machine by virtually all accounts.

Of course, it would take time to realize that the physical beauty of the 916 would be matched by its racing prowess. At the hands of Carl Fogarty, Troy Corser, and others, the 916 (and the higher displacement models that followed it, but were essentially of the same design, the 996 and 998) proved itself the most capable racing machine derived from a production street bike.

So Ducati had created a motorcycle with the rarest combination of all, i.e., peerless aesthetics and superb functionality. As we look back after just a few months since the announcement of its successor, the significant place in motorcycling history occupied by the Ducati 916 only begins to emerge.

So after nearly a decade, with the 916 (then known as the 998) still sitting at, or near, the top of the superbike pecking order, and Tamburini having long since left Ducati, Ducati introduces the replacement: the 999. In our article dated July 17, 2002, we discuss the unveiling of the 999, and briefly outline its technical highlights. While, aesthetically, it clearly has not made the splash the 916 did in 1993, its functionality is the focus of this report.

When MD arrived at the North American press introduction of the 999 at Willow Springs Raceway in Southern California, Ducati engineer Andrea Forni briefly reviewed the technical aspects of the new design for journalists in a classroom setting. In addition to those design elements discussed in our preview article, Forni stressed the following.

|

Ducati’s Unique, Unequal Length

Exhaust Plumbing and Underseat Muffler |

Although only a small improvement in aerodynamics was achieved with the 999 (the 916/996/998 had superb aerodynamics, already), the 999 design focuses extensively on weight distribution and center of gravity. The rider sits lower on the 999, closer to the rotating axis of the motorcycle (and its center of gravity), and weight bias has been shifted towards the front wheel. This makes the 999 less wheelie-prone than its predecessor. This shift of weight to the front of the motorcycle can be increased further by moving the adjustable rider ergonomics to their most forward position.

Simply shifting the weight bias towards the front of the motorcycle has many beneficial effects on handling, beyond the simple fact that the bike is less likely to wheelie. Front end grip in corners is enhanced, and the bike is less likely to understeer on corner exists (while under power). One area where a shift of weight to the front of the motorcycle can be detrimental is braking.

Under heavy braking (such as under race conditions), the shift of weight to the front of the motorcycle is greatly exaggerated, and the rear wheel can lift (we have all seen a “stoppie”). Engineer Forni explained that due to the lowering of the center of gravity on the 999, and an increase in length of the swingarm (the 999 swingarm is 15mm longer), weight shift due to braking forces is reduced, and the 999 is less likely to lift the rear wheel under heavy braking during a race. In other words, the lower center of gravity gave Ducati the best of both worlds, more weight over the front end, and a reduction in rear wheel lift under heavy braking.

The 999 also features CAN line technology, allowing two wires carring digital pulses to do the work of literally dozens of wires under a traditional system. This saves weight and complexity, and allows the instrumentation, for instance, to provide more usable data to the rider (such as lap times).

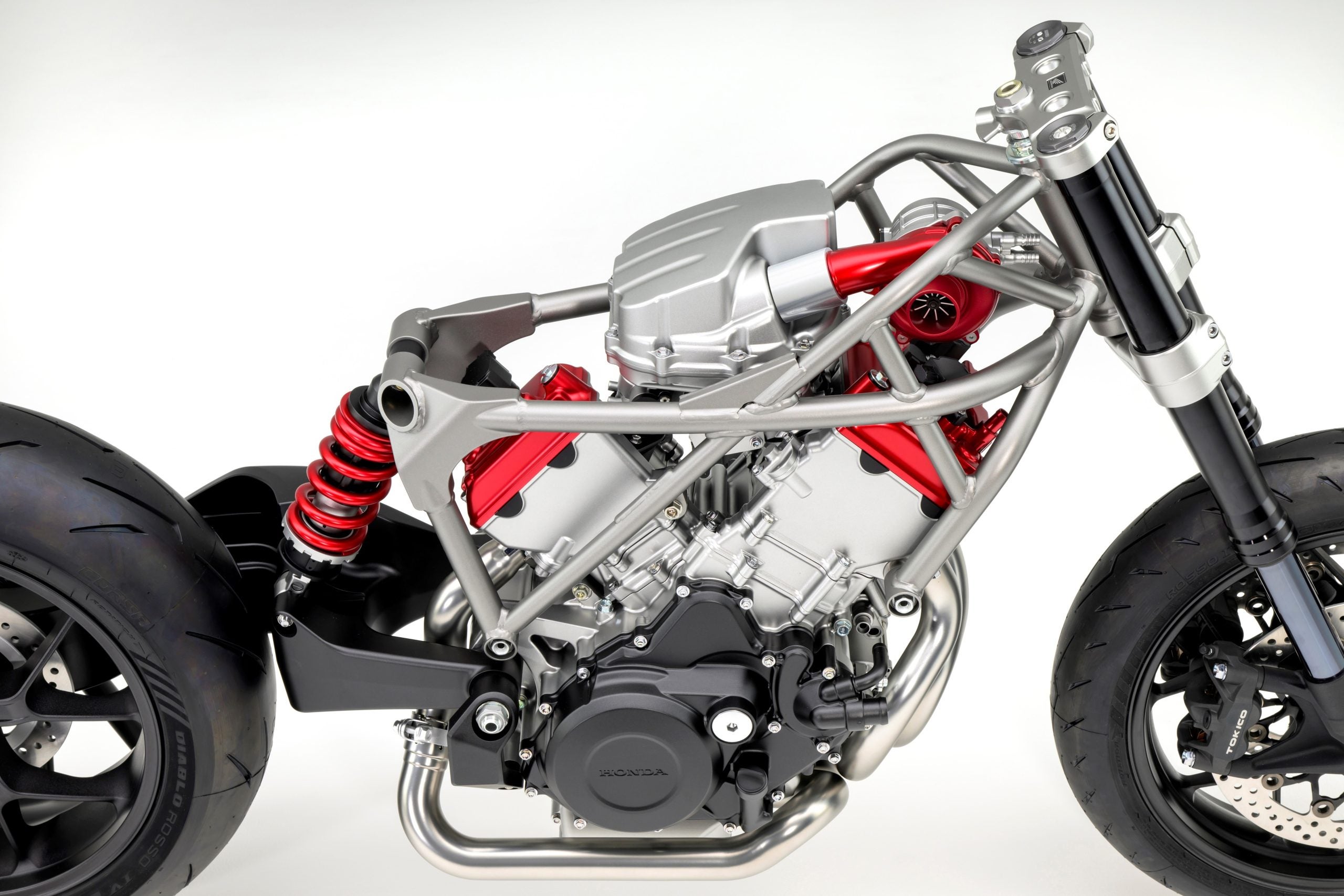

Although narrower than its predecessor, the trellis frame of the 999 duplicates the stiffness of the 998’s frame. Ditto for the larger, two-sided swingarm of the 999 (longer, but just as stiff as the old single-sided arm).

What follows is the account of MD associate editor Willy Ivins of the 999 track test at Willow Springs. Willy writes in the “first person”, because his mother taught him that he is the center of the universe. Take it away, Willy:

Willow Springs, known as The Fastest Road In The West, is my “home track”. I race here every month on a 125cc GP bike, and all of my experience here is on small bore two-strokes. I do have track time on four-strokes, including Yamaha’s R6, and the Honda RC51, but not at Willow. When Dirck told me I’d be riding Ducati’s new flagship there, I was excited, both because it was to be my first ever press intro, and also because I’d finally get to see and ride what must be one of the most anticipated new motorcycles of 2003.

This event also presented a new challenge for me as a rider – to pilot a large, four-stroke street bike through the sinuous 9 turns of Willow Springs, at higher rates of speed than I am used to, since my 125 is only capable of 130ish mph. I don’t have any experience with the 998 that this bike replaces, or any of its previous iterations, for that matter. I did spend considerable time testing Honda’s 2002 RC51, both on the street and at Califronia Speedway.

Reports of pre-999 ergonomics that would make a masochist wince, brakes that had owners thumbing pages of their favorite aftermarket catalogs, and clutch pull effort that could make a Gold’s Gym regular feel weak, registered in my mind, but not as much as the meaty torque of the engine, the stable (if high effort) steering -and precise handling. The stability, in particular, would come in handy at a fast road course like Willow, and hopefully Ducati had left this ingredient in the mix.

Looking at the 999s (14 of them) parked in the pits, I have to say that the fresh look of the 999 is very good, and is a welcome change with its own appeal. Comparisons between the looks of it and the 916-era super bike may border on apples and oranges, though. Nonetheless, I am here to ride and not much of the bike is visible while riding.

At 9:00 a.m., as promised, there is a rider’s meeting to discuss flag meanings, entry and exit of the pits and a reminder is issued that we’re not here to race, but to enjoy and evaluate this new motorcycle. For me, making my first press intro a good memory places a high profile bookmark in the “do not crash” portion of my mind. After the rider’s meeting, we’re split into two groups. The “A” group goes out first, while the “B” group stays put and gets the tech portion of the bike’s design and features. Andrea Forni, the head of the Ducati Vehicle Testing department, gives a thorough, no B.S. run down of the bike’s design and why it was put together this way. Tech briefing concluded, it was time to ride. Before we could trip over each other getting to the bikes, we are told that some of the bikes have not reached their break-in mileage of 600 miles yet, and that these bikes have an artificial rev limit of 9500 rpm, until passing the 600 mile mark. Luckily, the first bike I go to has 720 miles on it – woohoo!

I fire up the bike and immediately, I note how quiet it is. After putting on my helmet and gloves, I swing my leg over the bike. It feels small, especially in the middle. With a narrow mid section, my fairly short legs are not splayed out so much and it is easy to get both feet on the ground. Pulling in the clutch is not difficult, it’s pretty much on par with everything else available, as a matter of fact. Engaging what I thought was first gear, I start to pull out of the pit area. At first I thought Ducati had put in a really tall first gear, but then realized that I had actually put it into second gear. I needed to remember that this is a street shift pattern. Still, the engine pulled the taller ratio smoothly and without protest from the clutch.

Rolling out onto the track for the first session, I take it easy. During this familiarization time, I am able to notice that the ergonomics are very agreeable. I don’t feel like I’m doing a handstand, or that my legs are folded up like a jack knife. On the biposto model, the seat and gas tank are not adjustable as on the monoposto model, but the footpegs are set to the middle of their adjustment range, and the bike has a nice, balanced feel. The windscreen that works well in the wind tunnel with a fully tucked-in rider does very little, protection-wise, for the rider when they are not in that racer tuck. I see double-bubble style windscreen sales skyrocketing.

Throttle action is light, but travel is long, requiring a repositioning of the hand for wide open throttle (WOT) onto the straights. The engine revs cleanly, quickly and forcefully, reaching the rev limiter in a manner more associated with four-cylinder engines. Also, the motor is remarkably vibration free – up to 8500 rpm. After 8500, the bars buzz in your hands like low frequency tuning forks.

Braking is superb. Very good initial bite, great feel at the lever, and all the power you need, haul the bike down from speed. 320mm rotors appear very thin, and have a groove machined into the edge to assist in heat dissipation. Put simply, the new four piston, four-pad Brembos put the reputation of last year’s brakes to shame.

Track Drawing Courtesy of Willow Springs Raceway Website

After acclimating myself to the bike’s characteristics, i.e., engine braking, which the 125 does not have, and the bike’s physical presence, which the 125 doesn’t have, either, I got down to the business of the bike’s behavior at race track speed.

After a mediocre drive onto the front straight, I was able to catch 6th gear for only a couple seconds. Speed before slowing for turn one was an indicated 148 mph. Braking for turn one, I catch 3 downshifts. Despite having break-in mileage, the transmission is still a little stiff and requires conscious effort to complete the shifts before the turn-in point. Trail braking is a non-event, as the bike remains neutral in its steering manners, and releasing the brake does not have the bike falling in, no matter how abrupt. Drive out of the corner is trademark Ducati V-twin, as it shoves you down the straight from one corner to the next. Torquey, traction-finding drive can be had from as low as 6000 rpm, but best results come at 7000 and up.

Turn two is a fast right-hander that has the bike on its side for quite a while. Typically, there is only one smooth line through the corner. On this bike, there are many smooth lines as the suspension, adjusted to its middle settings, soaks up everything and makes the track feel freshly repaved. Middle of the range suspension settings means the bike takes a quick moment to settle in. The lean angle necessary for the corner speed made possible by the Pirelli Super Corsas has the footpeg touching intermittently, but not dragging. With this going on, the bike remains a solid feeling unit, with no squirm or wiggle. Driving out of two, the bike doesn’t squat or wallow as the turn flattens out at the exit, it just accelerates.

One upshift to 4th gear before turn three, and then you’re hard on the brakes, which remains a two-finger effort, and you downshift to 2nd gear. Blipping the long travel throttle for each downshift proves troublesome. Not enough throttle cable movement makes matching the rpms to road speed for the next lower gear a difficult task and requires more thought and effort than it should. A shorter travel throttle would be nice. The outside of the approach to turn three has some ripples in it that I normally avoid like the plague on the 125, but with the bigger bike, I need to set up wider to maintain the corner speed. Braking over the ripples had the bike diving quite a ways, and the bike was moving around a bit but the forks never bottomed. As before, turn-in on the brakes was neutral. A late apex for this corner has you pointed straight uphill early, encouraging the rider to get on the throttle sooner. This can be perilous, because the turn goes from a positive camber at entry to the apex, to nearly off camber at the exit. The 999’s fuel injection works extremely well, on par with Yamaha’s ’02 R1, and allows the delicacy required to keep from tearing through the edge of the traction envelope. To some degree, the long travel of the throttle may be responsible.

Turn four can be approached a number of ways, either by hugging the inside line, or double-apexing it, or somewhere in between. None of the possibilities seems to make much difference in lap times, but the double-apex option sets you up for a straighter run down the hill. It’s a tricky part of the track that, if you try to make up too much time lost elsewhere, will see you losing the front before the second apex, or highsiding after the second apex. It’s best to set your speed for this corner at the entry and then maintain it until you’ve reached the exit. Going from full lean on the left to the right for the turn three/turn four transition is about the only part of Willow where you can get any insight to the flickability of the 999. With the steering head set at the lazier 24.5 degree adjustment, a little more physical input and time to make the transition was required than if it were set to the quicker 23.5 degree angle. As it was, the bike settled in and tracked through turn four with a reassuring feel. Opening the throttle could begin fairly early without drama to get a drive down the hill. I hang onto second gear down the hill, carrying good speed and getting into the rev limiter just before the braking point.

Turn five can be a little deceiving, and like turn four, presents the options of an early or late apex, depending on your preference or situation with a rider ahead. Again, I go for the late apex, since it gets your drive up to the crest of turn six started sooner. Sometimes a rider will carry too much speed (or thinks they have) into five and grabs a little front brake. Since the corner goes downhill and slightly off camber, it is a turn where it is easy to lose the front. Lightly trail braking into this corner requires good front end feel and good feel at the brake lever. Front end feedback is pretty good, giving me enough information, but could be improved one of two ways, or both – by decreasing steering head angle and/or moving the seat to the forward position, which is possible only on the monoposto version. Scrubbing off that one last mph just after the turn-in point, I am able to get into the throttle fairly hard at the exit for the drive up to the crest of turn six.

Turn six is a slight right-hand turn that snakes over a small hill leading to the back section of the track. The more powerful bikes can be seen wheelying down the backside of this hill, and if due care is not taken, a bike can be blown off the track with its front wheel in the air. Exiting turn five in second gear, I short-shift to third, setup for the middle of the track to avoiding the sharper plateau on the inside line and wait until after the crest of six to go to WOT. Even doing this, I feel the front tire maintaining only light contact with the asphalt. No drama at the front, though – no threat of a tankslapper, not even a headshake. Again, torque is plentiful and the drive over the hill, even though restrained, is still very enthusiastic.

Clicking up through the gears, acceleration is urgent and as the velocity rises, the track narrows. Going through “turn” 7 (actually, it’s just a slight left-hand kink) I catch fifth gear and with a little muscle, dive for the inside line at the beginning of turn eight. On a calm day, this turn is its own adrenaline super gulp, but with the wind that has inevitably come to play, discretion is in order. Besides, abrasion testing of the fairing is not part of the program. With 150 mph showing, I can say I’ve never entered this turn this fast before, since my 125 is not capable of anything near 150 mph. But yet, aboard the 999, it feels natural and with each lap, I try to convince myself to keep the throttle pinned (in fifth) to catch sixth, but never do it. As in turn two, there are bumps and ripples, but I don’t feel them on this bike, it just tracks through the corner like a train on rails.

Turn nine is a decreasing radius corner that can give even the bravest rider a moment’s pause, and can give the rest of us a bit more than a moment…. Setting up wide for this corner I catch one downshift, then another shortly after as I get closer to the apex. I hold the wide line until I clearly see the cone at the inside of the corner, and then cut straight for the cone, all the while dialing in the throttle. The rear tire digs into the pavement and the engine shoots the bike out of the corner with 8300 rpm showing in third gear. The two-stage shift light, one flash 200 rpm before redline and another just 100 rpm prior signals the rider that the next gear must be engaged to keep the fun level up. Revs rise very quickly, causing the shift light to flash like a turn signal circuit with one bad bulb. Getting to sixth gear with a good drive onto the straight has me holding the throttle open a solid four seconds before the brake marker, reaching an indicated speed of 154 mph. Although acceleration is quite rapid, it is linear and unthreatening. Wheelies struggle to overcome the longer swingarm, which doesn’t fit well with the wheelie crowd, but it does help the rider log quicker lap times at a race or during a track day.

Throughout the day, when the groups would switch, you could not count on getting the same bike you had last time. As a matter of fact, you could count on *not* getting the same bike. This made making changes to suspension, ride height and ergonomics an exercise in futility, as each rider had their own adjustments they wanted to make. Too much time would be absorbed in the pits wrenching when you could be out on the track. I just rode the bikes as I got them and made note of the different feel of each. I did get a session aboard a monoposto unit that had its suspension set towards the firm end of the scale. Supposedly, the seat & gas tank had been moved to the forward position, but I did not confirm this. On the brakes, through the corner and over the hill in six, this 999 was more precise and composed and did not take time to settle into the corner as the bikes on standard settings would, and I set my fast time aboard this bike.

I engaged in a couple experiments during my last session, one of which had the transmission in fourth gear for the whole lap, the other was seeking out the areas I knew to be bumpy to see if I could get the bike to misbehave at all.

In fourth gear at 6K rpm, the motor did not pull as hard out of turn one as it had from 8K, naturally, but still accelerated enthusiastically. The tach dropped all the way to 4500 rpm at the apex of turn three, and while drive up the hill was not inspiring, the motor pulled smoothly and willingly up the tach face. The handy on-board lap timer showed the bike to be about 4 seconds per lap slower with the one gear being used. Although the bike turned in a predictably slower lap time, this exercise highlighted the flexibility and power of the testastretta engine.

As far as the bumps were concerned, turns two, down the hill out of four and a couple lines through turn eight took their best shot at upsetting the 999, but all failed. The trade off for such compliance over the rough stuff (on the softer, “standard” suspension settings) is a little less precision and less ground clearance. The softer settings, combined with the velcro-sticky Pirellis (and my 195 pound ready-to-ride weight) allowed me to touch down both pegs and the sidestand. Just a grazing, mind you, nothing touched down hard, and there were no such incidents on the more stiffly setup monoposto.

After doing all those laps at Willow at speed, I was not tired or sore at the end of the day. Instead, I was grinning and wanting more.

I was very impressed by the 999’s performance at the track. Up to 8 tenths riding, the middle-of-the-road suspension settings are quite capable of getting you around the track in respectable time. How respectable? Most laps, I was in the mid to low 1:31s, all while weaving through more than a few slower riders, giving plenty of room during passes. On the monoposto model that had the stiffer setup, I logged two non-consecutive laps of 1:30.7 according to the on board lap timer, on fairly shagged (but still grippy) tires. Only a slightly loud voice in my mind that kept repeating, “what if you crash?” prevented me from tweaking the suspension to my personal preferences and going for 29s, something that this bike, with nothing more than tires and suspension setup, is certainly capable of.

For a bone stock, street motorcycle to go as fast as this one does at the track on as-delivered settings tells me that the basic geometry and balance of the chassis is very good . . . a good starting point for anyone to adjust for themselves to go fast and be comfortable. I’m looking forward to having one on the street for a while so I can evaluate how it behaves in the environment where a vast majority of these 999s will live out their lives……