It wasn’t too long ago that industry observers wondered whether Kawasaki had fallen asleep. The brand once known for standard setting high performance seemed to be falling behind. Some of its best selling, and most respected, models had become badly outdated, including the Concours and KLR650. Even in the sport bike category, Kawasaki seemed to be lagging with products like the ZX-9R, which was a nice bike, but hardly cutting edge in the open class.

After a pep rally, of sorts, attended by several journalists at Kawasaki headquarters in Irvine, California several years ago (where the head of Kawasaki USA Marketing said the company was “getting back to kick-ass, high performance motorcycles”), things started to change. The old Kawasaki was coming back.

This point was underscored for me in September of 2005 as I sweltered in the heat and unbelievable humidity at the Orlando, Florida Walt Disney Resort. Sitting in the stands with other journalists and Kawasaki dealers from throughout the United States, I furiously drank water in an effort to keep pace with the relentless flow from the pores of my body. Frankly, I wanted to go back to my air conditioned room. Then, something truly interesting, and even startling, happened. In the context of an industry running scared from the Suzuki Hayabusa (“. . . our lawyers won’t let us build something like that!”), Kawasaki rolled out the 2006 ZX-14, brazenly stated it would be the most powerful production motorcycle on the planet (as the Hayabusa tumbled from the top step of the podium), and had the big bruiser lay down a smokey burnout that had the audience choking thirty rows up. You could almost hear the engineers at Kawasaki barking “To hell with the lawyers, we can build this thing and make it rideable, and safe!”

Less than six months later, my son Alex and I rode the new ZX-14 at the press introduction in Las Vegas, Nevada. Those engineers did combine incredible power and speed in a usable, safe package. On an unfamiliar track, and an unfamiliar bike, and with virtually no drag racing experience, Alex ripped off a 9.83 second quarter mile in Vegas on the ZX-14. No drama . . . just an exciting ride on the back of a well controlled bullet.

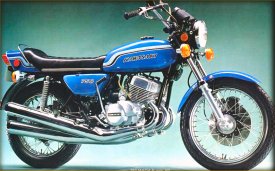

The 1972 750cc H2 two-stroke triple was easily the quickest accelerating bike of its day . . . but a little bit scary to ride

I had recently ignored it, but thoughts of Kawasaki’s motorcycle heritage started to flood back into my mind. The source of these thoughts was not history books, or Kawasaki promotional literature, but my own memory banks.

I have written before about the occasional drag race that ended in front of my home (in the early 1970’s) between neighborhood rivals piloting a Honda CB750 (MD’s Bike of the Century) and a Kawasaki Mach 3 (the 500cc, two-stroke, triple designated the H1). Sometimes I would just hear the wailing from my bedroom; sometimes I would see it out of the bay window in my living room; and on those rare (but memorable) occasions I’d be mowing the front lawn as the throttles shut down and the brakes were clamped just yards away from me. Roughly 14 years old, I had already been riding dirt bikes for several years, and dreamed that some day I could pilot a street bike like one of these two machines.

Kawasaki upped the ante of its H1 with a 748cc, two-stroke triple known as the H2 in 1972. When my local dealer Steve Hurd got his hands on the first H2, he gave me a ride behind his shop. After wisely advising me to lock my fingers around his waist, Hurd accelerated hard and the bike went into a low power wheelie that seemed to last the length of a block. After dismounting, Steve showed me how the H2 could easily spin up the rear tire. At 15 years old, motorcycles were my drug of choice, and I was shamelessly addicted.

Despite their fierce straight-line performance, neither the H1 nor the H2 handled very well, and the two-stroke street bike era was coming to an end. In 1973, Kawasaki introduced the Z1, a four-stroke 900 that was meant to out-gun Honda’s CB750. Other noteworthy high performance models followed, including the GPZ900 and the ZX11.

Although Kawasaki appeared almost fearless at times when it came to the introduction of high performance motorcycles, as I would learn first hand in Japan, for more than 100 years, Kawasaki has embraced, and excelled at, the manufacture of products that operate in dangerous environments.

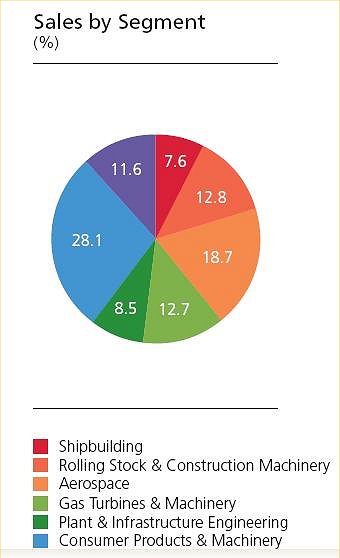

Kawasaki Heavy Industries (KHI), the conglomerate that manufactures motorcycles through its Consumer Products & Machinery Division, exceeded 12 Billion U.S. Dollars in sales in 2007. Consumer Products & Machinery (not only motorcycles, but watercraft, ATVs, general purpose gasoline engines and industrial robots) accounted for 28.1% of KHI’s net sales in 2007. Here is a pie chart with the breakdown.

KHI's 2007 sales were split this way. Motorcycles fall under the "Consumer Products and Machinery" category.

KHI’s Heritage and Cultural Context

KHI has its roots in the business activities of Shozo Kawasaki in the 1800s. Understanding KHI requires knowledge of its heritage and cultural influences.

Shozo Kawasaki was born in 1837 on the island of Kyushu, Japan to a merchant father. To say that Shozo “lived in interesting times” would be an understatement.

During Kawasaki’s youth, Japan was largely cut off from the West. Only the harbor at Nagasaki allowed Western trading ships to enter, and prior to 1853 (when Shozo Kawasaki would have been 16), the Dutch were the only Western traders allowed into Nagasaki on a regular basis.

This all changed when the United States sent Commodore Matthew C. Perry into Tokyo Bay demanding that diplomatic and trade relations open between Japan and the United States. A treaty between Japan and the United States in 1854 made this a reality, and, within four years, other large Western nations, including Great Britain, France and the Netherlands created their own treaties with Japan, and began trade activities.

When Shozo Kawasaki was 30 years old, Shogun rule, and the official role of the Samurai warriors (as the only armed force in Japan) came to a rather abrupt end when the reigning Shogun was defeated by forces (led by Samurai) aimed at installing a young emperor. In turn, Japan adopted the Imperial Charter Oath, which led to the modernization and industrialization of Japan, in part, by breaking down class barriers and encouraging all Japanese to reach their potential.

Shozo Kawasaki, like all Japanese, must have felt the weight of these historical events. Kawasaki’s involvement in the shipping industry, however, made these changes even more profound in his own life.

One year after Commodore Perry first sailed into Tokyo Harbour, Shozo Kawasaki was 17 years old, and working in Nagasaki as a tradesman. Just ten years later, and only three years prior to the end of Shogun rule in Japan, Shozo Kawasaki started his own shipping business in Osaka. This business ultimately failed when a storm sank his cargo ship.

Kawasaki suffered a number of close calls during shipping accidents that convinced him Western ship design was superior to the typical Japanese design of his era. Despite his business failure as a 27 year old, Shozo Kawasaki persevered, learned from his mistakes, and ultimately founded a ship yard in Tsukiji in 1878, a date that is frequently considered the start of the current Kawasaki Heavy Industries organization. Along the way, Shozo Kawasaki worked with a Samurai from his hometown of Kagoshima in the sugar trade.

Although the direct influence of the Samurai was dying in Japanese society, their moral authority (the code of Bushido) was still strong and likely influenced Shozo Kawasaki in the development of his own business ethics and strategy. “Forged by the sword”, these principles came to guide entire cultures.

Bushido and Chivalry are as closely related in character as the Japanese Samarai and the English Knight. Both were a warrior class that were forced by their perilous pursuits to develop strict codes requiring honor, courage, loyalty and forthright dealings.

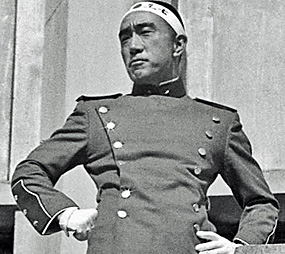

Arguably the most famous person in Japan at the time, Yukio Mishima, author, martial artist and body builder committed seppuku the same day this photo was taken of him on the balcony of the Tokyo Defense headquarters in 1970

Although chivalry still has some waning influence over American society (it influences our military code of conduct, for instance), Bushido infused Japanese with a very deep sense of honor and propriety that still exists. Examples of this include the Japanese public’s mixed reaction to the dramatic, failed efforts by famous author Yukio Mishima (thrice nominated for the Nobel in Literature) to revive strict allegiance to Bushido and Japanese Imperialism, which led to his seppuku (ritualistic suicide) in 1970, and the enduring popularity of the Japanese play Chushingura as reported in The Japan Times on December 15, 2002.

Throughout my trip to Japan, the politeness of the Japanese was striking. The Zen-like focus on the customer by service employees (on airplanes, in coffee shops, etc.) was very impressive, and starkly contrasted with many service employees here in the United States.

Japan, like every other country on the planet, is changing, however. Western influences are diluting traditional, cultural mores. Nevertheless, for a company like Kawasaki, which is rooted in the era of Shogun rule, traditional cultural influences cannot be overlooked. This includes the devotion of employer to employee, and employee to employer. Life-long employment in Japan is a tradition, and although modern economic necessities have sometimes intervened, it still influences the culture within a company like Kawasaki, where employees have a level of devotion to their employer, and visa-versa, that goes beyond what is typically seen here in the West.

The editor greeted by Senior Vice President Shinichi Tamba at KHI World headquarters, Kobe, Japan (Jan Plessner of Kawasaki Motors USA looks on)

Ships, Planes, Trains . . . and Motorcycles

If you have often wondered why it is called Kawasaki Heavy Industries, you are about to find out. In Part Two of this series, we will go inside KHI’s major manufacturing facilities. Stay tuned.