A low center of gravity is generally considered a good thing on a race bike, but Ducati indicates that raising the center of gravity (by raising the seat height and the handlebar height) on Nicky Hayden’s Desmosedici has made the machine much more rideable, and consistent. How? By heating the tires more quickly, and consistently.

As you probably know, attempting to tame the Desmosedici almost ended the career of Marco Melandri, and caused former champ Nicky Hayden innumerable headaches earlier this year, before Hayden seemed to figure something out and finish on the podium at Indianapolis (followed by qualifying on the second row at Misano, before being knocked out of the race by another rider). The higher center of gravity allows the bike to dive more on the brakes and squat more under acceleration — typically considered negative behavior from a racing motorcycle, but apparently necessary to warm the tires more quickly for mortal riders like Hayden and Melandri (Casey Stoner is so hard on the gas from the start, he has no problem bringing the tires up to temperature, quickly). It is hard to argue with results, and Hayden has certainly improved. Let’s see how he does in the remaining four races.

MD Readers Respond:

- I am usually not a big fan of technical specs as I am just a street rider, but I find particularly interesting your article today about the center of gravity for the Ducati and how affects braking and tire warming, I never would of thought.

On a different note I am sad to report that my 2000 Ninja ZX9R went up for sale last week. Here in Québec, license plates have tripled, going from 325$ two years ago to 1035$ for summer 2009 and are supposed to hit 1435$ next summer…just too much for me since I don’t ride all that much anymore. My interest in sport touring bikes just isn’t there and even less for custom bikes…looks like I may dust the moutain bike and hit the trails again!

Keep up the great work, I do tune in everyday to your web page. Pierre - *Ahem* Casey’s mortal, too. Just ask some dude named Valentino if you need

proof. 🙂 Brett - I actually learned that dive and squat could be a good thing (At Skip Barber in Monterey) because it increases traction on the tire being compressed. The flip side, of course, is that it reduces traction upon the tire being unloaded. This is something that would be a difference for the entire race, and not just the 30 seconds or so sooner that a tire might reach operating temperature.

If this is the case, and of course I have no idea if it is, it’s fascinating to me that another racing advantage comes from giving the racer more control over the bike, rather than insulating the rider from the bike as is done by traction-control systems and ABS. The other instance of this I find fascinating, is Yamaha’s cross-plane crankshaft — which gives Rossi, Lorenzo and Spies more feel and control over their rear-tire traction, rather than less.

Interesting times! Jett

- In today’s article you claim that a low center of gravity is good on a

race bike; but Kevin Cameron wrote an interesting article ages ago about

how a low center of gravity can cause understeer and other problems, and

that while it is desirable in a car, it is not desirable in a motorcycle,

where mass centralization is more important. The upside down design of

the ’84 NSR500 is usually given as an example of why a low center of

gravity is a bad thing. Any thoughts on this? - Your editorial about raising the center of gravity reveals how misunderstood this factor of motorcycle geometry really is. Contrary to popular belief, and the loud pronouncements by BMW marketing, lowering the center of gravity on a motorcycle results in largely negative behaviours in any condition other than straight line travel. Since the principle desired ride characteristic of motorcycles is easy roll into and out of corners and any speed (tipping into the lean with as little effort as possible), the ideal placement of C of G is centered along the roll axis of the combined motorcycle/rider mass. This is an imaginary horizontal line around which the bike/rider tilt left or right.

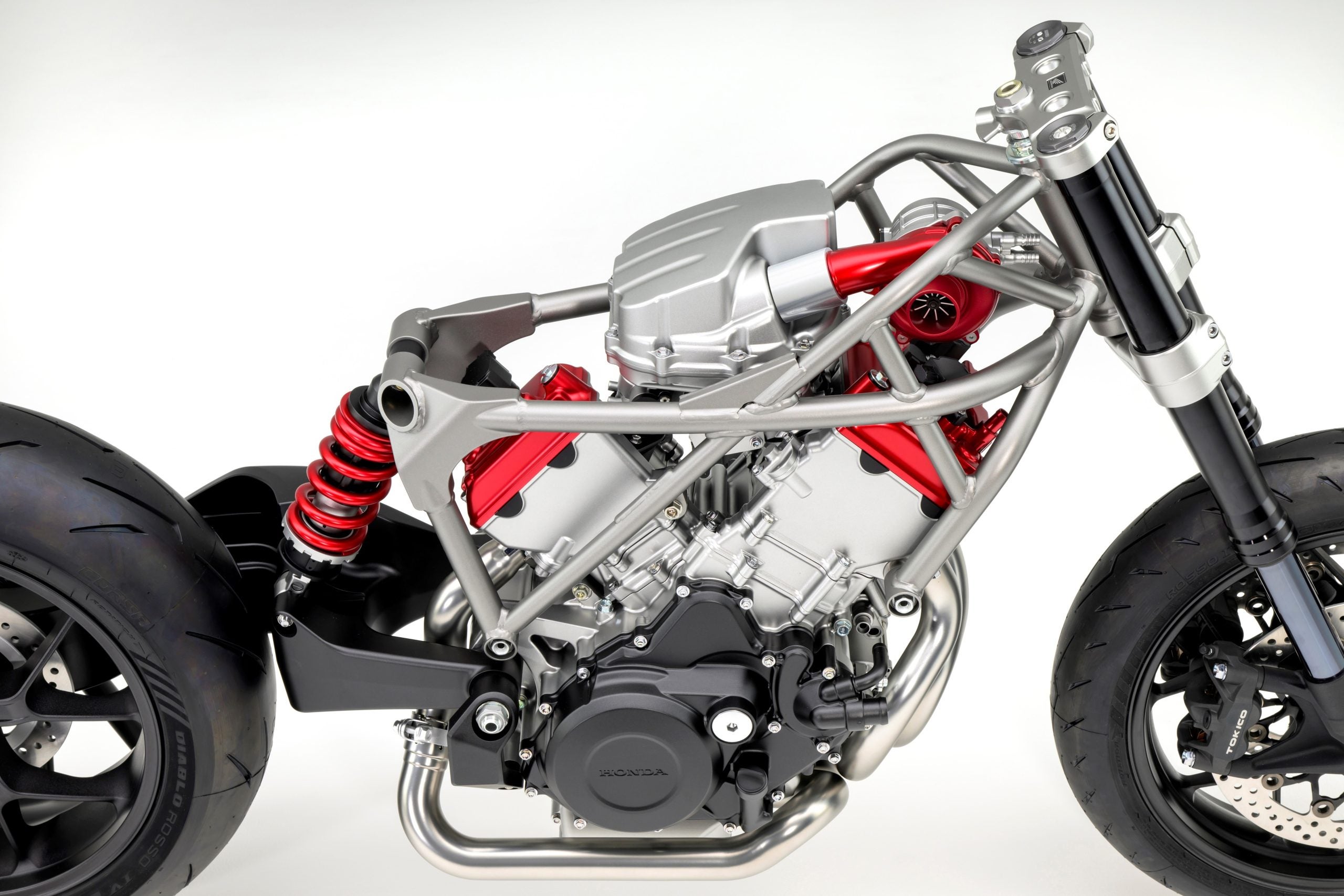

The Japanese discovered this in the mid 1980s after experimenting with machines like the Yamaha FZ “slantblock” 750 (which BMW successfully copied 20 years later with the K1200S, much to the motorcycle industry’s amusement) and Honda’s bizarre “upside-down” NSR500Grand Prix bike. Both examples were very stable, but this made turning the machine difficult and resulted in band-aid compromises such as reducing wheel diameter in an effort to reduce gyroscopic effect, and reducing steering angles, both of which were dangerous enough to offset any stability benefits of the low C of G.

If you look at any Japanese sport/racing bike from 1995, 2000 and 2005 you will see that the engine crank axis moved consistently upwards, forwards, and that the cylinder block (on inline fours) is more vertical (even the BMW SS1000 has followed suit). This is how gigantic, heavy motorcycles like the Goldwing ride so easily even at low speeds around tight corners. Total mass is less important than balance.

The point is that there is no mystery behind the Ducati Desmoseidici, beyond that it is a difficult handling racing motorcycle. No one has been able to ride it consistently other than Stoner, unlike the M1 and RCV212 which have been successfully ridden by a wide variety of people, proving how much more manageable they are. Ducatisti have to face facts: no amount of will power, passion or superbike success can equal 40+ years of Grand Prix competition success. Michael