Last month we posted our comparison test between three bikes raced in Daytona Sportbike, a new class developed by the new AMA Pro Racing that pits a variety of middleweight – and bigger – sportbikes against one another. Our conclusions? That the riders were still the most important component of these bikes; our lap times showed the three stock bikes were pretty evenly matched.

What happens when you throw a full factory race kit at one of them? When you ride the machine in Daytona Sportbike factory trim? I was invited to Elkhart Lake, WI, home of the 4-mile-long, 14-turn Road America racecourse where Buell Motorcycles had a fleet of 2009 models ready to run on the track. But the big treat was getting a ride on one of the Richie Morris Racing (RSR)/Bruce Rossmeyer Racing/GEICO Powersports1125R racebikes.

Luckily, the bike is a lot more wieldy then its name. Hopping aboard the bike for my three laps, I note the seat is higher and there are lots of other little differences – controls, bars, rearsets – but the bike still feels familiar, as I’ve been riding 1125Rs and 1125CRs all day. The bike is also equipped with a GP-style reversed shift pattern and a quickshifter; something to get used to in addition to a race-spec engine, suspension, brakes and tires. At least it has an electric starter; no need to toss it, as the rules allow the team to add weight to the bike to keep it legal for the class limit of 380 pounds (post-race) for Twins.

The engine barks through the open race exhaust as I fire it up for the third time (yes, I stalled it twice), toe it up into first and head out pit lane towards turn one. First impression: smooth motor, pulling to redline quicker that stock, with a throaty (but not-too-loud) roar from the plain-looking underslung muffler. Turn 1 comes up quickly, and the bike tips in faster than the stock bike. I spend the first lap carefully getting used to the bike’s extra power, brakes and suspension capability. There’s also a little more drivetrain lash, a result of the chain-drive conversion.

After I pass the start/finish, I start to get a little more aggressive. I’m very impressed by the smooth, easy operation of the DynoJet quickshifter. Just a slight prod downward with the left boot and the next gear slides into place; no need to roll off the throttle. Why doesn’t every sportbike have one of these? A momentary brain fade gets me to downshift into first at a good clip rolling into the turn 11 chicane, but the slipper clutch saves me from a highside as the engine shrieks and bounces off the rev limiter. I try to use the brakes into the next turn, instead of the expensive motor to slow me, and I find much better feel and bite from the kit pads, rotor and brake line.

The motor feels strong and there’s no question it’s faster than a stock bike, but power delivery is progressive and vibration was the same as the stock motor. It feels like it has about 10-15 extra horses. The class rules don’t allow for a lot of engine mods (pistons, rods, crankshaft and many other parts must be stock and unmodded), so it’s not surprising the Rotax mill feels like a carefully built and lightly breathed-on stocker.

By the third lap I can pretend I’m a seasoned pro, with my knee skimming the pavement and the bike disappearing beneath me. I’ve ridden a few professionally prepped racebikes, and the ones I like best feel like very good, well-developed streetbikes. This 1125R has smooth fuelling, makes power everywhere, suspension that soaks up bumps but doesn’t wallow, is as comfortable as the street version yet is well suited to racetrack work.

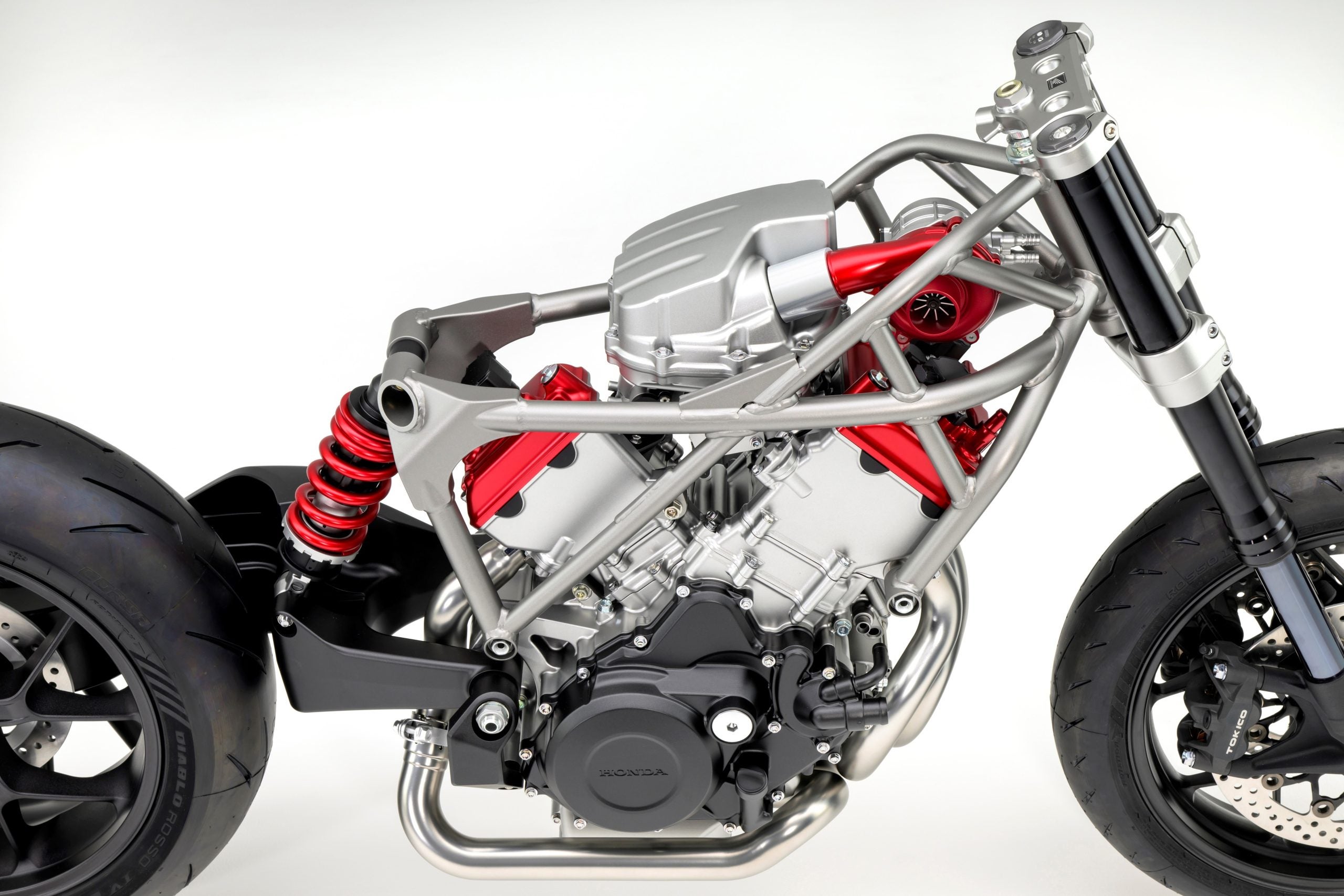

Back in the pits, David McGrath, Buell’s Racing R&D leader, debriefs me and I ask him about what’s in the race kit. It has a lot of the stuff you’d expect, like race bodywork (in glass or carbon-fiber), race suspension cartridge and shock, lightweight subframe and fairing stay, and of course the race exhaust system and programmable ECM. There are other bits as well, like an abbreviated wiring harness and GP-style shifter. Sounds like big money, especially that chain-drive conversion, which features billet-aluminum end pieces to accommodate chain adjustment. It’s a good kit, designed by Buell engineers and based on stock parts, and it all works well together. Must be expensive.

But it’s not. “Around $20,000,” says David, and I remark that sounds inexpensive for such a comprehensive list of parts. “Including the stock bike,” he adds, and I’m flabbergasted. For $20,000, a race team – or privateer – can field a bike that’s capable of winning AMA roadraces? A visit the next day to the Buell race shop confirms this, as Erik and his raceshop crew proudly display the race parts on a table for us. They’re available to licensed roadracers, and to help pay for them, there’s about a million bucks of contingency money for national and regional roadracers out there; remarkable for a small-volume manufacturer, but not surprising, given Erik Buell’s privateer-racing roots and parent company’s Harley-Davidson’s longing to win races. You can visit Buell’s Racing Support page for more info.

MD Readers Respond:

- MD Reader Claudio wrote: “The official reason given is that offers close racing, but under similar reasoning one could conlude that because the Buell is the most inferior of the twins, it needs the most advantage. The purpose of racing is to make a product better and in the process showcase it. The Japanese 600’s have a considerable head start compared to the Buell.”

Claudio is making the mistake of defining “better” in sport bikes as horsepower per cc of displacement. There are many other factors: Handling, weight, engine width, gyroscopic effect, effect on chassis dynamics, engine braking, fuel efficiency (i.e, how much a rider has to carry for a race), tire wear, and power band.

Buell is building a street bike that they happen to race. The Japanese manufacturers are building race bikes that they happen to sell for street use. Buell has long recognized that street riders need a broad power band, lots of torque, and longevity. That’s what they get with the V-twin configuration. They also get a narrower engine. As a street rider, I like not having to row through the gears when I come around a corner and find myself behind a slow-moving vehicle. I like being able to pass by just rolling on the throttle. I like riding at highway speeds with an engine turning a more relaxed RPM (under 4K rpm gets you to 80 mph on an air-cooled Buell sport bike).

Something else that people don’t consider is how much air an engine pumps. A 1200cc engine spinning 7,000 RPM is moving the exact same amount of air as a 600cc engine spinning at 14,000 RPM. Assuming equal efficiencies (friction and cylinder filling/emptying), they should make the same amount of horsepower.

When you go into your dealer to buy a sport bike for the street, do you want the one that works the best or the one that has the highest redline? I rode to work on a 1200cc Buell today and even had a bit of fun with a guy on an R6 who had to shift furiously as we worked our way through traffic. I didn’t get black-flagged, disqualified, or subject to a tech inspection tear-down when I arrived at the office. Fred

- I heard the interview with Roger Edmondson this past weekend and the first big question was about parity or superbike spec rules. Your article dealt with the motorcycle and its performance with a closing about how economically feasible it is. There was one thing omitted, but it wasn’t necessarily the purpose of the article, the technological deficit with other comparable race bikes. For most of the history of World Superbike Racing, the rules have given twins a displacement advantage. The problem I think is that the rules are now brand specific in AMA, Ducati 848, Aprilia 1000, and Buell 1125. The official reason given is that offers close racing, but under similar reasoning one could conlude that because the Buell is the most inferior of the twins, it needs the most advantage. The purpose of racing is to make a product better and in the process showcase it. The Japanese 600’s have a considerable head start compared to the Buell. If Ducati (which is a much smaller company than Harley) (I see Buell to Harley like Lincoln to Ford, different name and models but tied to the parent company) can build a bike (also not a twin) capable of winning in MotoGP, then Buell can make a real supersport or superbike that can win on an even playing field.

About 10 years ago, I bought my first new motorcycle. I was interested in a sportbike and my budget was $11,000. That meant almost any bike that wasn’t a Ducati. So I researched the big four’s litre bikes and found out about Buell. The idea of an American bike was interesting, however I found out it meant a Harley engine and less HP. I bought a Suzuki TL1000R.

The step towards liquid-cooled engines for both Harley and Buell was a step in the right direction. If Buell is to compete with 600 sportbikes, they might have to switch to a 2 to 4 year model cycle. I don’t think this is the best economic climate right now for that direction, so instead they could get a headstart with their electric and/or alternatively powered sportbikes. Claudio